Our HP Omen 45L’s 285K CPU operated 1.4GHz below its actual spec and we analyze why it performed so poorly

The Highlights

- Our HP Omen 45L came equipped with a 285K, RTX 5090, and a case with an “Omen Cryo Chamber”

- The system not only has unbelievably bad thermals for its cryo chamber for the 50 seconds it actually runs at the Intel guidance, but it also kneecaps performance after 50 seconds to make the 285K be worse than the 265K in all-core workloads

- The HP Omen 45L is the worst pre-built gaming PC we have ever benchmarked and reviewed.

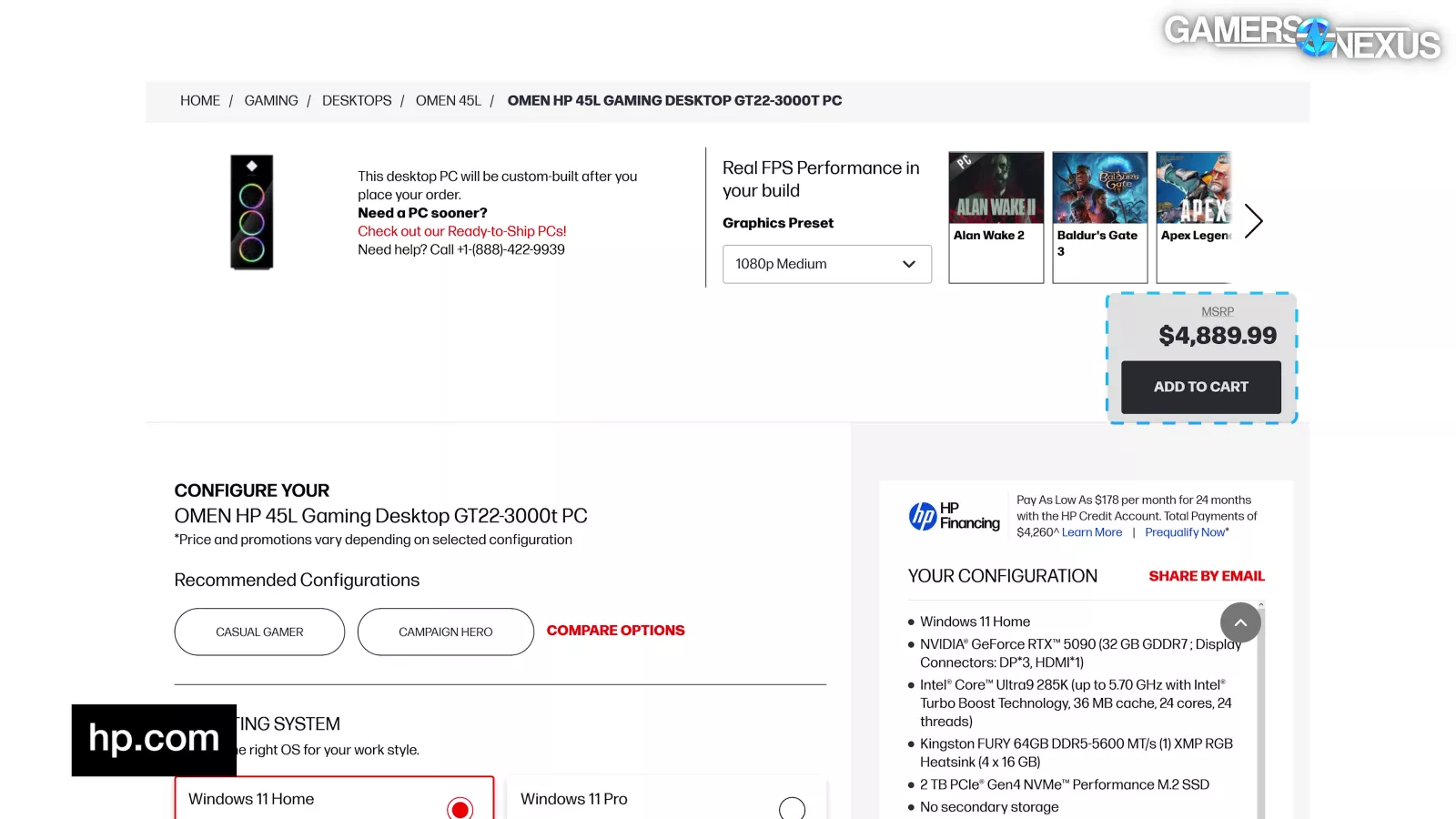

- Original MSRP: Approximately $4,890

Table of Contents

- AutoTOC

Intro

The HP Omen 45L is the worst pre-built PC we’ve ever reviewed.

The CPU is operating 1.4 GHz below the actual spec, which makes the $530 Intel 285K perform worse than a $260 265K, while operating somehow both below the power budget and above the thermal limit at 105 degrees Celsius in some cases. HP says that fixing the power limit to be stock for the 285K VOIDS YOUR WARRANTY, all the while its operating system is filled with spying bloatware and telemetry to harvest your data even after paying nearly $5,000 for a gaming PC with the memory preconfigured to an abysmal DDR5-4800 somehow.

Editor's note: This was originally published on September 4, 2025 as a video. This content has been adapted to written format for this article and is unchanged from the original publication.

Credits

Test Lead, Host, Writing

Steve Burke

Testing, Writing

Jeremy Clayton

Camera, Video Editing

Vitalii Makhnovets

Tim Phetdara

Writing, Web Editing

Jimmy Thang

This computer is incomprehensibly bad. HP might have just dethroned Dell as the official low bar for our pre-built reviews going forward.

But there’s more.

There’s also this video that seems to be a mix of the Bill Nye intro edit re-cut by someone on some bad acid, featuring a miniaturized woman inside the computer, some text about respecting "mother," keeping heat off of mother with thermal pads, and then a reference to motherboards.

Overview and Marketing

Today we’re reviewing the HP OMEN 45L GT22-3000t pre-built PC. As you can see, the name really rolls off the tongue.

It’s got a top-tier price of about $4,900, an Intel Ultra 9 285K CPU, 64GB of RAM, a 2TB Gen4 SSD, and what HP says is a “dazzling” NVIDIA RTX 5090 GPU. That’s good, because we hate the 5090s that aren’t bedazzled.

The marketing copy will continue until the pre-builts improve. The OMEN 45L apparently has room for the kitchen sink, as long as that kitchen sink doesn’t use a PCIe slot.

“The OMEN 45L is a one stop, can't stop, shop for DIY performance mastery. Dream, adapt, overcome.”

First of all, that’s not what DIY means. This is literally the opposite of DIY.

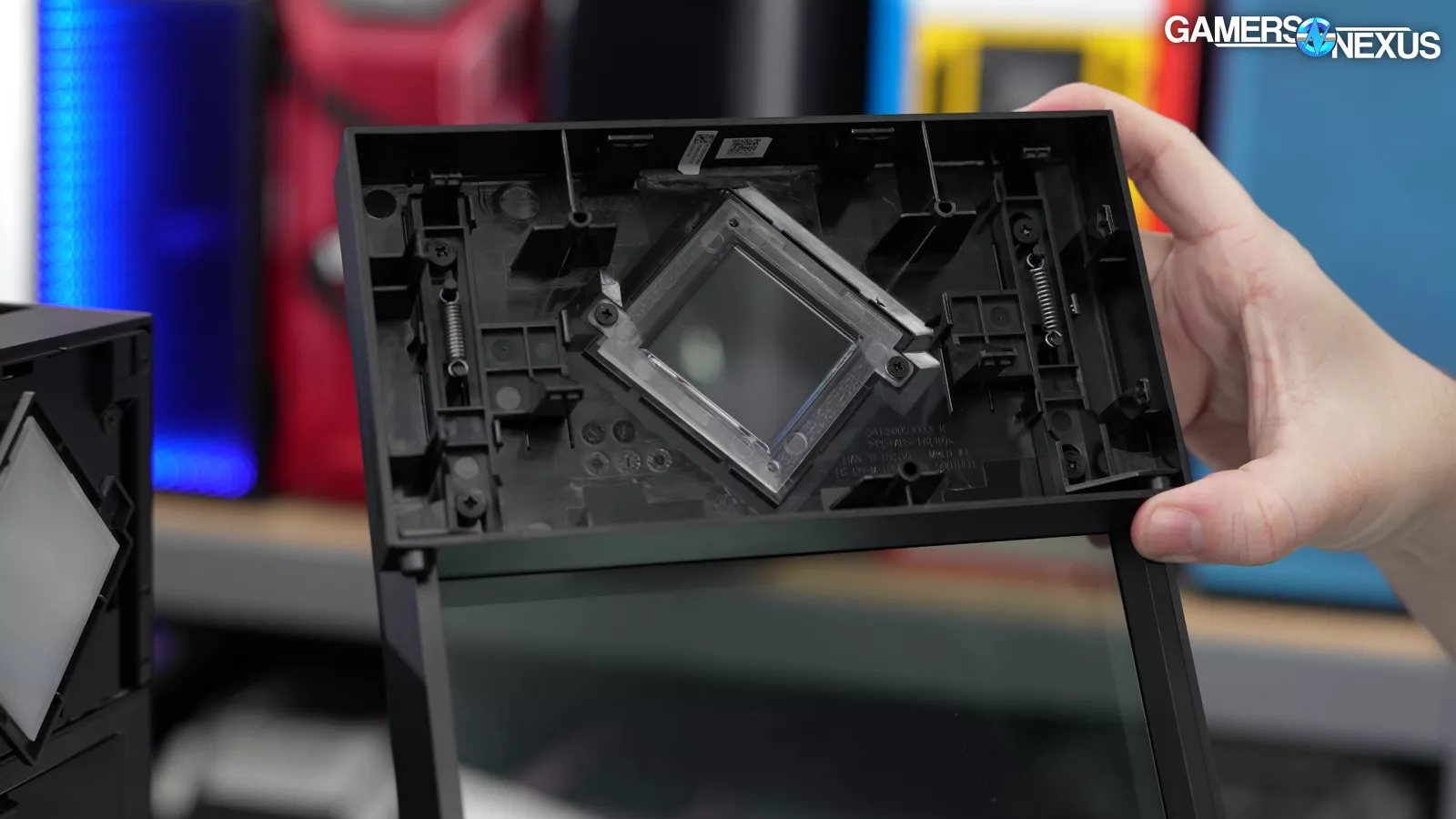

The Omen 45L has a patented “OMEN CRYO CHAMBER” that isn’t cryogenic but is technically a chamber.

We’re not sure why putting a radiator in a box gets a patent, especially since there is prior art, but welcome to intellectual property of things the USPTO doesn’t understand.

The chamber should prevent any pre-warmed exhaust air from the GPU from impacting CPU cooling. It also means the only way for that GPU exhaust to leave is through the single rear fan.

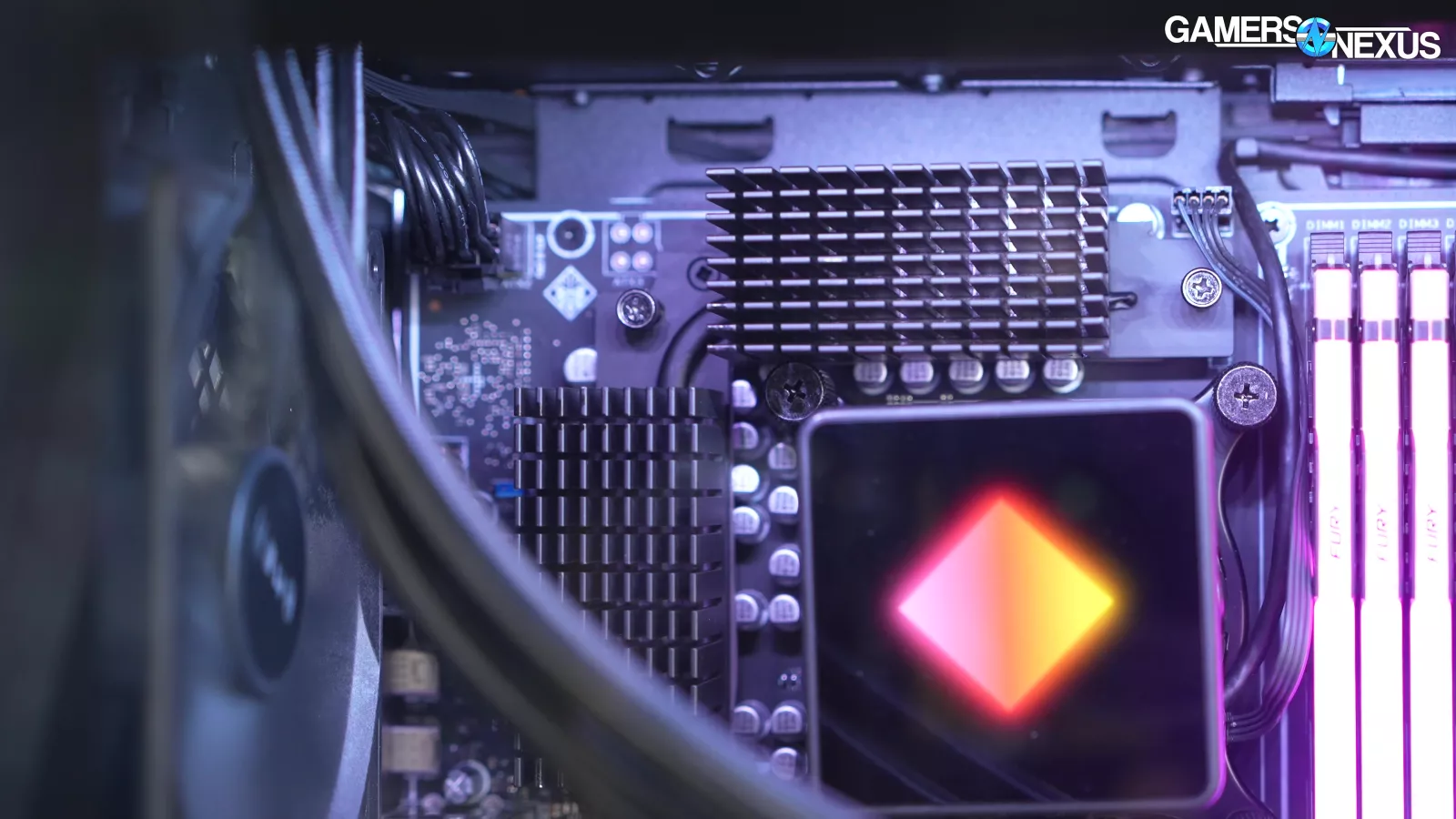

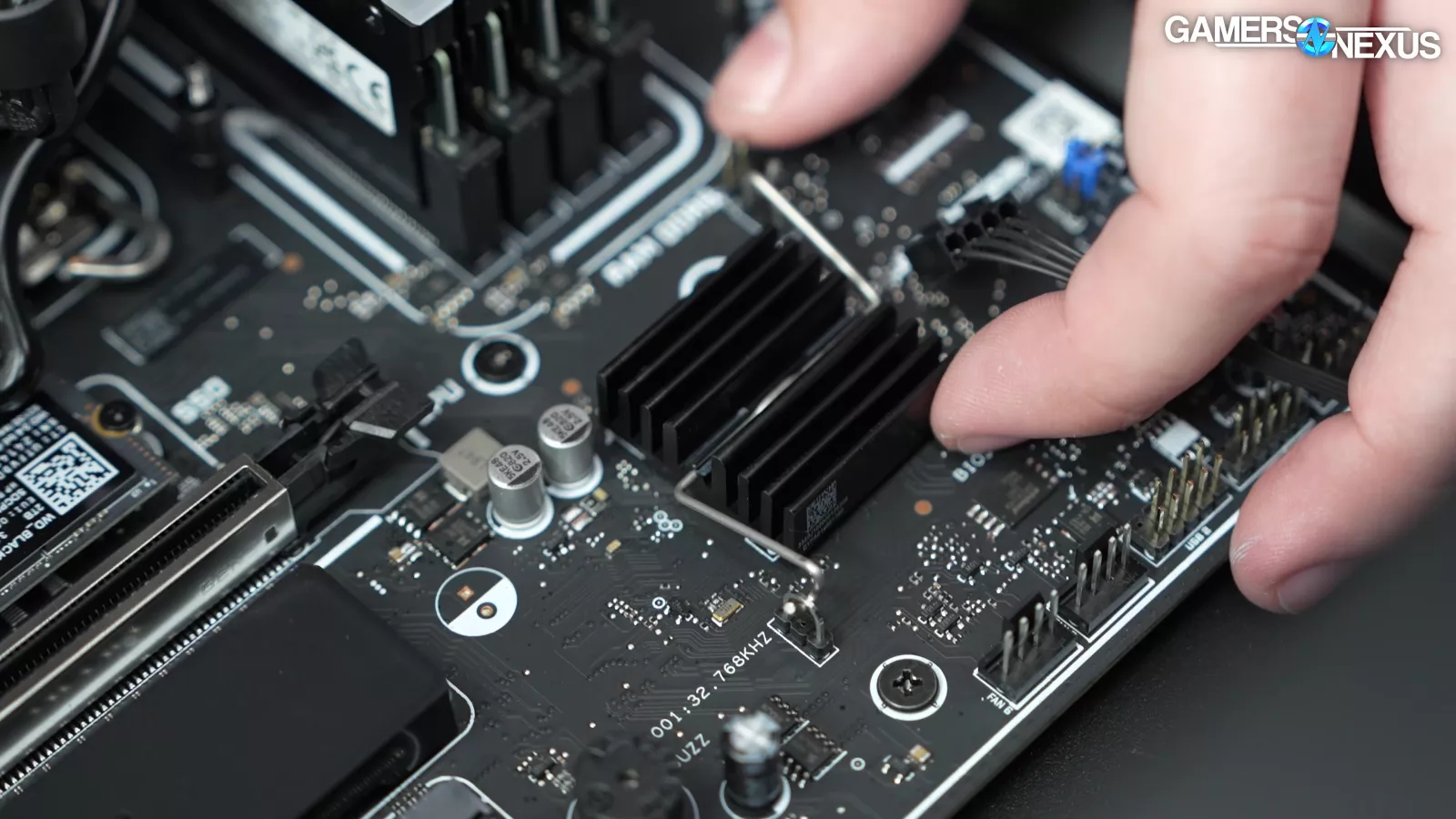

The Z890 motherboard itself is a strange mix of minimal rear I/O with a CMOS reset button, heatsinks that look pretty good for cooling the 14+2+1 VRM, all in an MATX package that doesn’t take advantage of the case’s ATX size that’s supposed to fit kitchen sinks. It’s a bizarre mix.

Parts and Value

HP OMEN 45L (GT22-3000t) Pre-built | Part and Price Breakdown | GamersNexus

| Part Name | DIY Equivalent Part | DIY Part Price | |

| CPU | Intel Ultra 9 285K | Identical | $550 |

| CPU Cooler | 360mm Liquid Cooler | Thermalright Frozen Warframe PRO 360mm | $75 |

| Motherboard | HP Z890 MATX | ASRock Z890M Riptide WiFi MATX | $220 |

| Memory | Kingston FURY DDR5-5600 64GB (4x16GB) | Identical | $236 |

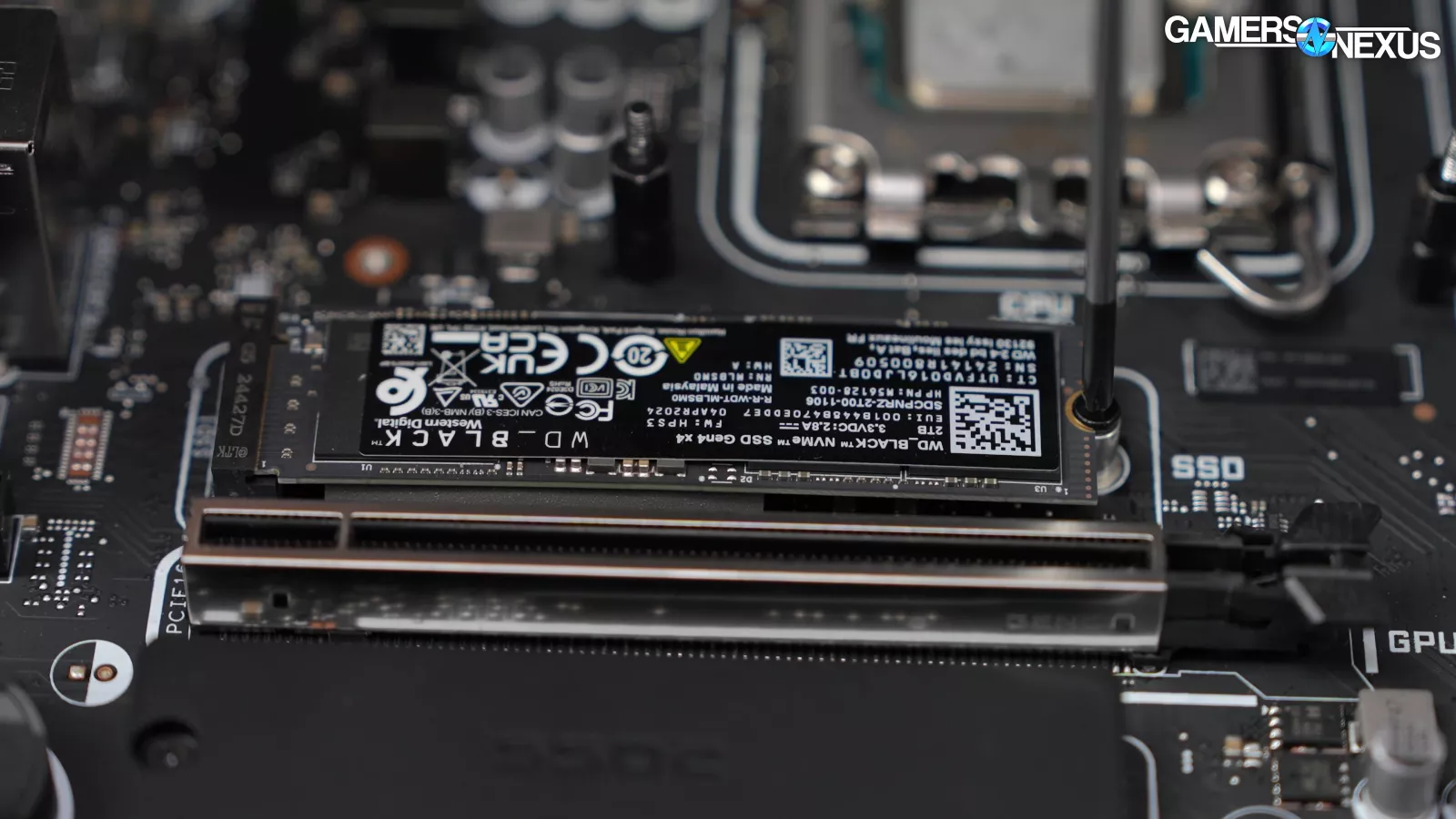

| Storage | 2TB NVMe M.2 Gen4 SSD | Silicon Power UD90 2TB NVMe M.2 Gen4 SSD | $98 |

| GPU | HP RTX 5090 | Zotac GAMING SOLID OC RTX 5090 | $2,400 |

| Case | HP OMEN 45L feat. "CRYO CHAMBER" | Montech AIR 903 MAX | $76 |

| Power Supply | 1200W 80Plus Gold | Montech CENTURY II 1200W 80Plus Gold | $125 |

| Pre-built Price: $4730 then / $4890 now | DIY Total: $3780 | ||

| Pre-built Premium Over DIY: $950 then / $1110 now |

Here’s a table breaking down the parts and price of the OMEN 45L versus a set of DIY parts. As usual, we matched identical parts where possible, and chose the most sensible replacements for the rest.

HP’s general part selection is “fine” for a very high-end build, but we have nitpicks. The first nit is more of a... whatever the opposite of a nit is, because the 285K is god-awful and HP makes it worse. It may be Intel’s best current consumer CPU, but AMD’s 9800X3D (read our review) outperforms it in games, and gaming is definitely the target audience. The 285K is also on a dead-end platform.

Using an MATX motherboard in an ATX case is technically fine, but restricts the user from adding any other PCIe card below the GPU, and we were told there’d be kitchen sinks.

The RAM choice is sub-optimal and made far worse by the fact that XMP wasn’t on, which is just really sad at this point. 64GB is what we want at this price, but not slow DDR5-5600, although that’d still be better than the DDR5-4800 it’s running at out of the box. That’s an insane combination that even a novice DIY PC builder wouldn’t make. Intel Arrow Lake has a strong memory controller – so we’d like to see 6000 minimum, or 6400 preferred, as 6400 is officially supported. It can even be cheaper RAM.

We paid $4,730 for the OMEN 45L a few months ago, but it’s risen to $4,890 at the time of writing. Normally, the prices come down. That puts the current-day price difference between it and a DIY build at $1,100, or 29% greater than buying these parts yourself. That’s unfortunately not unusual for a pre-built of this tier, but it has to be flawless for the value to hold up at all. The OMEN 45L is the worst pre-built we’ve tested as you’ll soon see, plus it’s just bad value.

Tear-Down

The PC’s “Cryo Chamber” is located at the top of the case. This design has been done before. It’s actually a really old school approach to radiators. What HP is trying to do is to separate the radiator from the rest of the system so that warm air is pushed off of it and doesn’t end up in the rest of the computer. The downside is that the PC doesn’t have fans in the top to help with cooling elsewhere.

At the front of the case, there are 2 buttons along both sides of the front panel, which allows users to take it off. It’s very complicated with some release mechanisms. Pulling the front cover off, however, reveals the case’s front fans and highlighted to us how the fans here have less than an inch of airflow. This design hinders performance.

Continuing our tear-down, we removed the case’s front dust filter, which is behind a sheet of glass. This is, again, bad for airflow.

We then proceeded with the tear-down by removing screws on the front of the case.

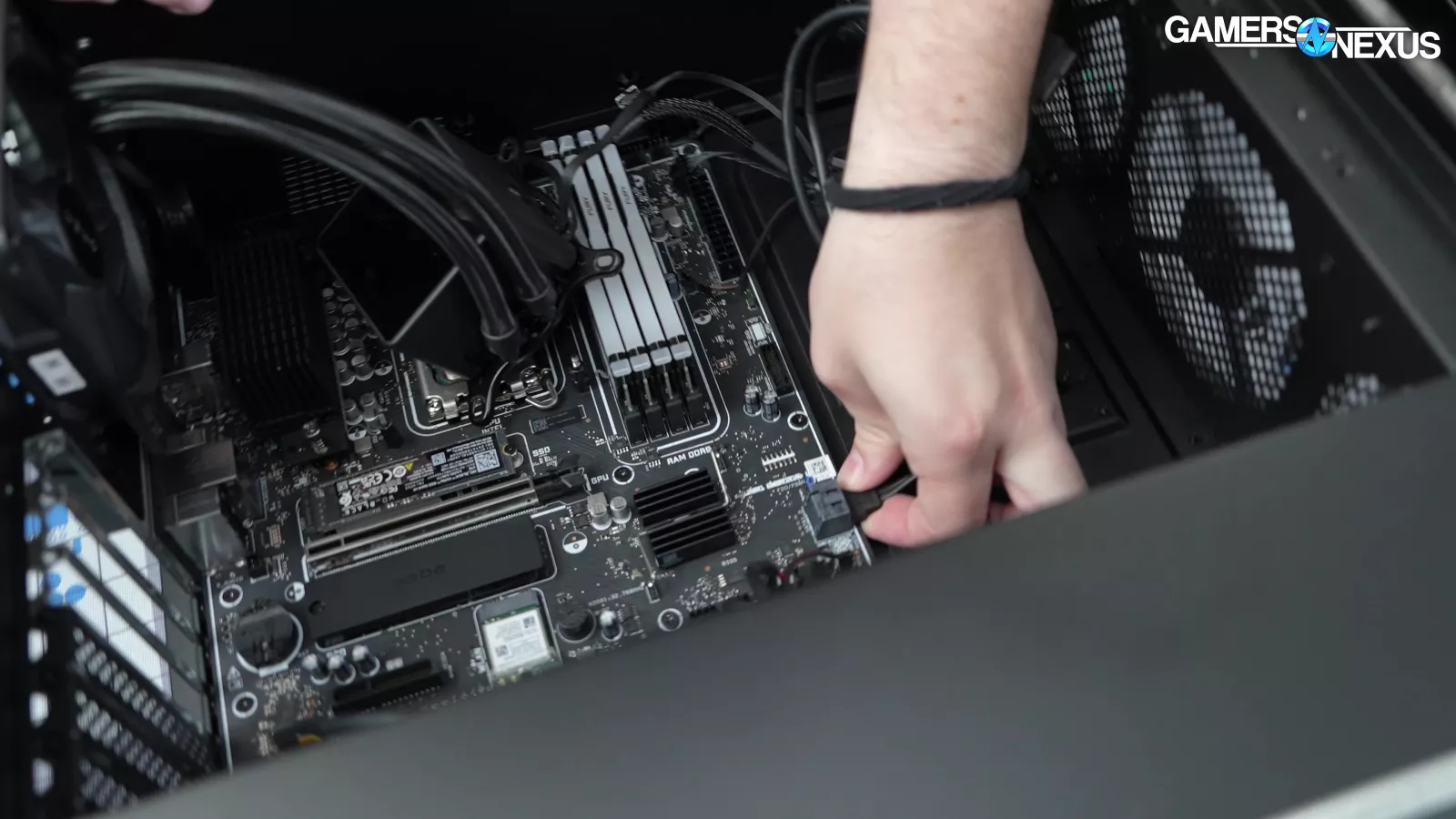

We then removed the computer’s glass side panel.

Taking a look inside the case, we noticed that the 12VHPWR cable has some hot glue on it for some reason.

We then unscrewed the Asetek cooler off of the CPU to see if we could get an understanding of why the processor was running so hot. Removing the cooler, we were able to confirm that thermal paste was used and that there was contact. We honestly thought we might have seen a “peel-before-installation” sticker still intact given its thermal performance.

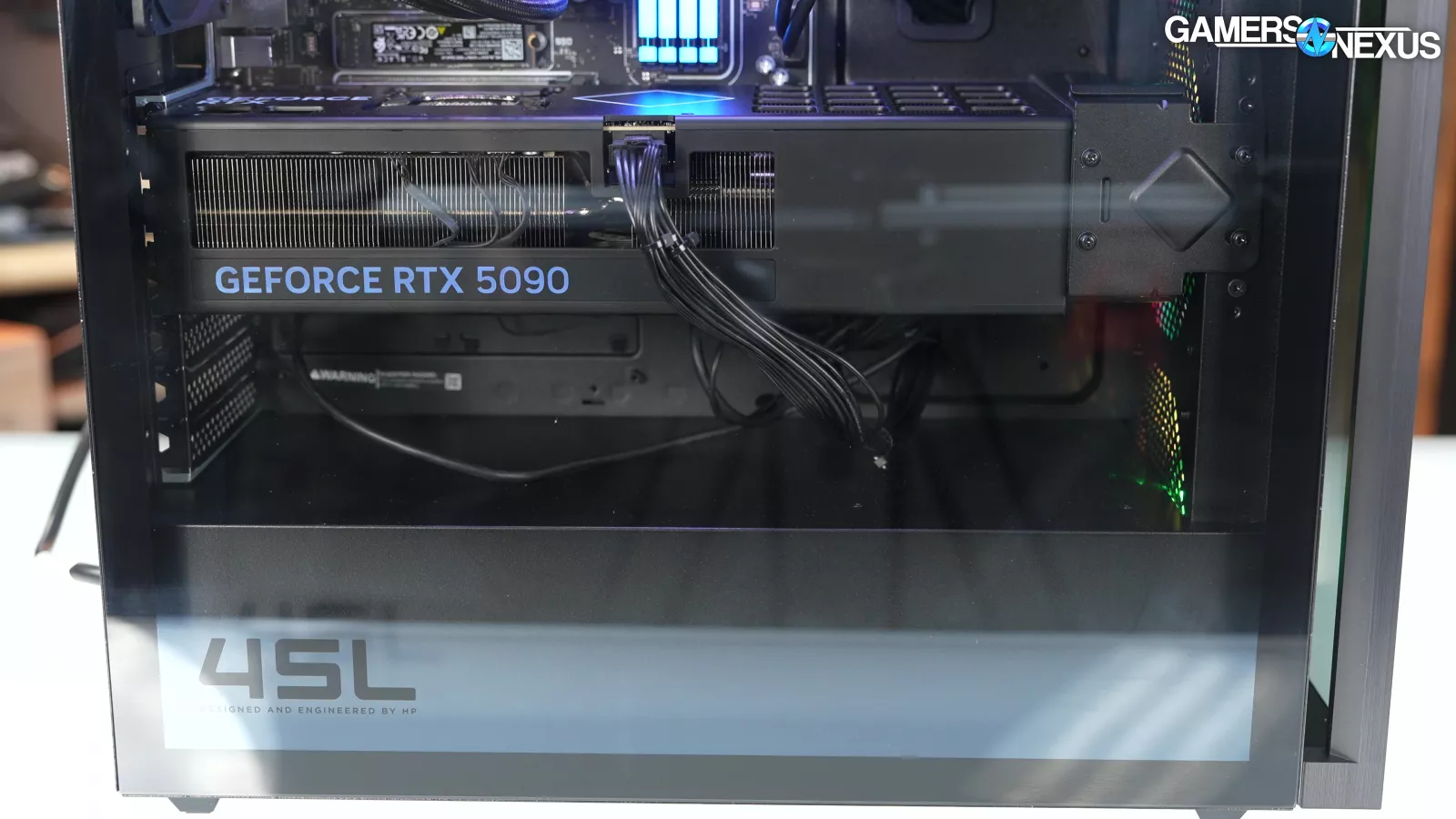

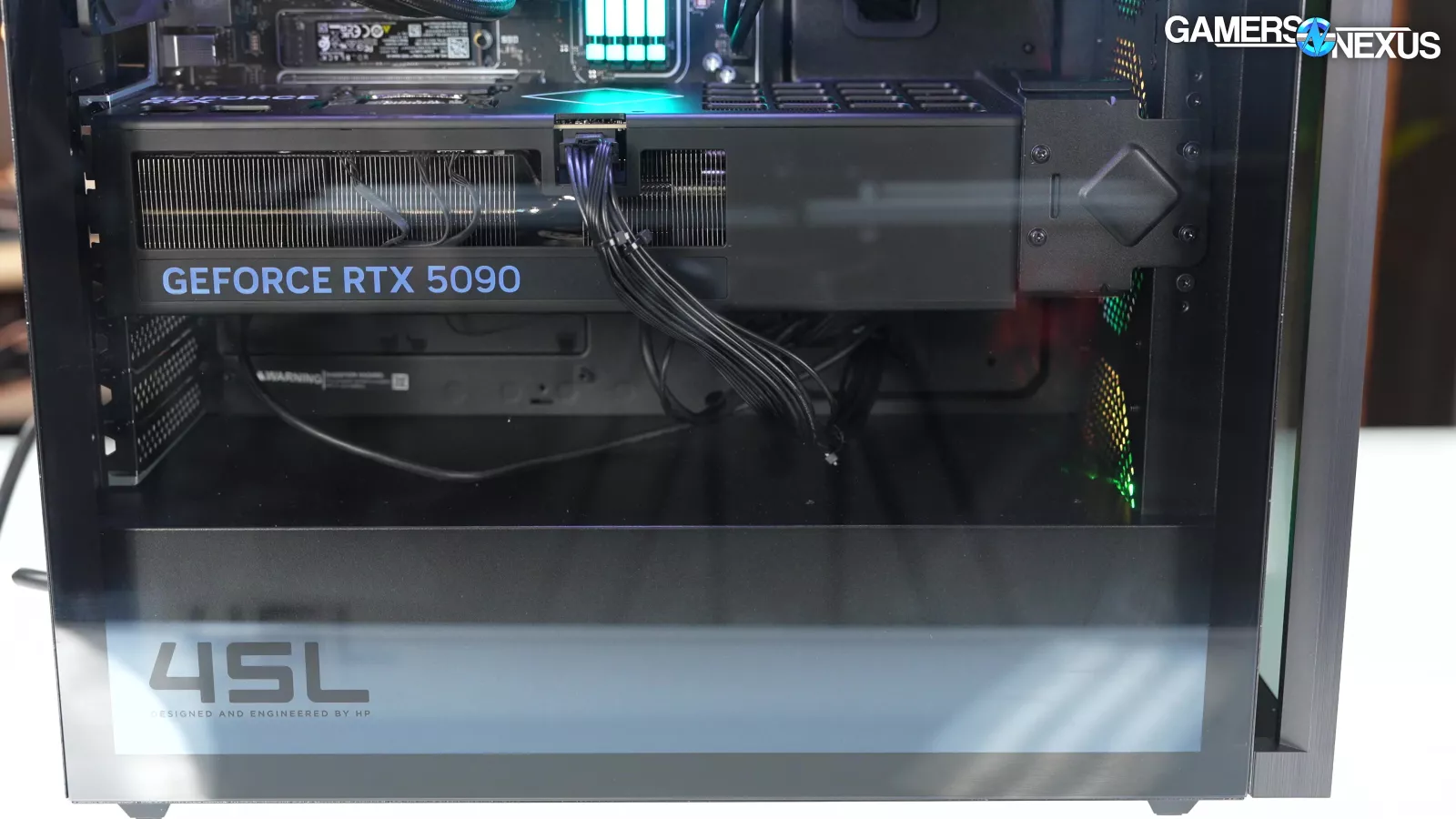

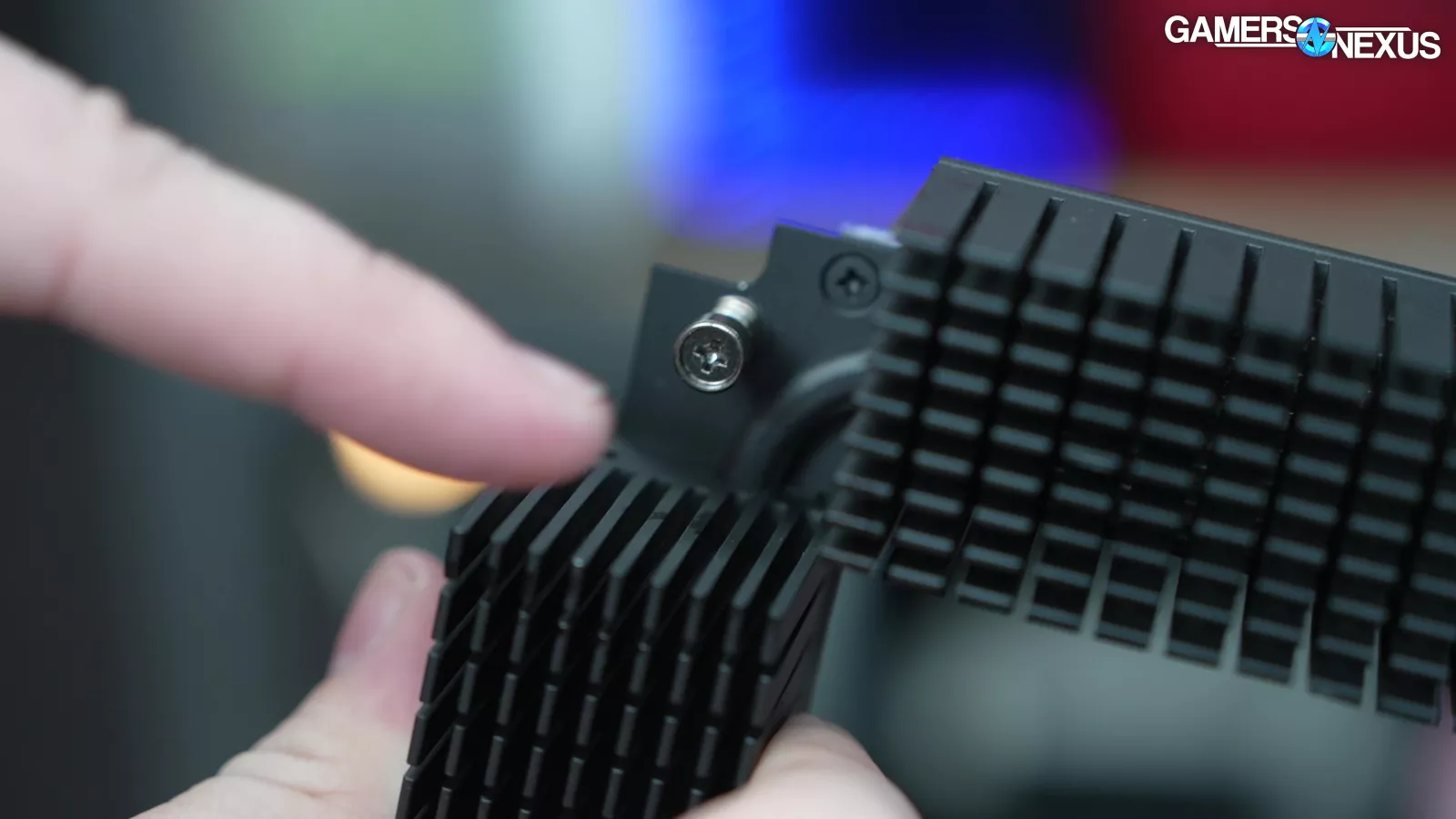

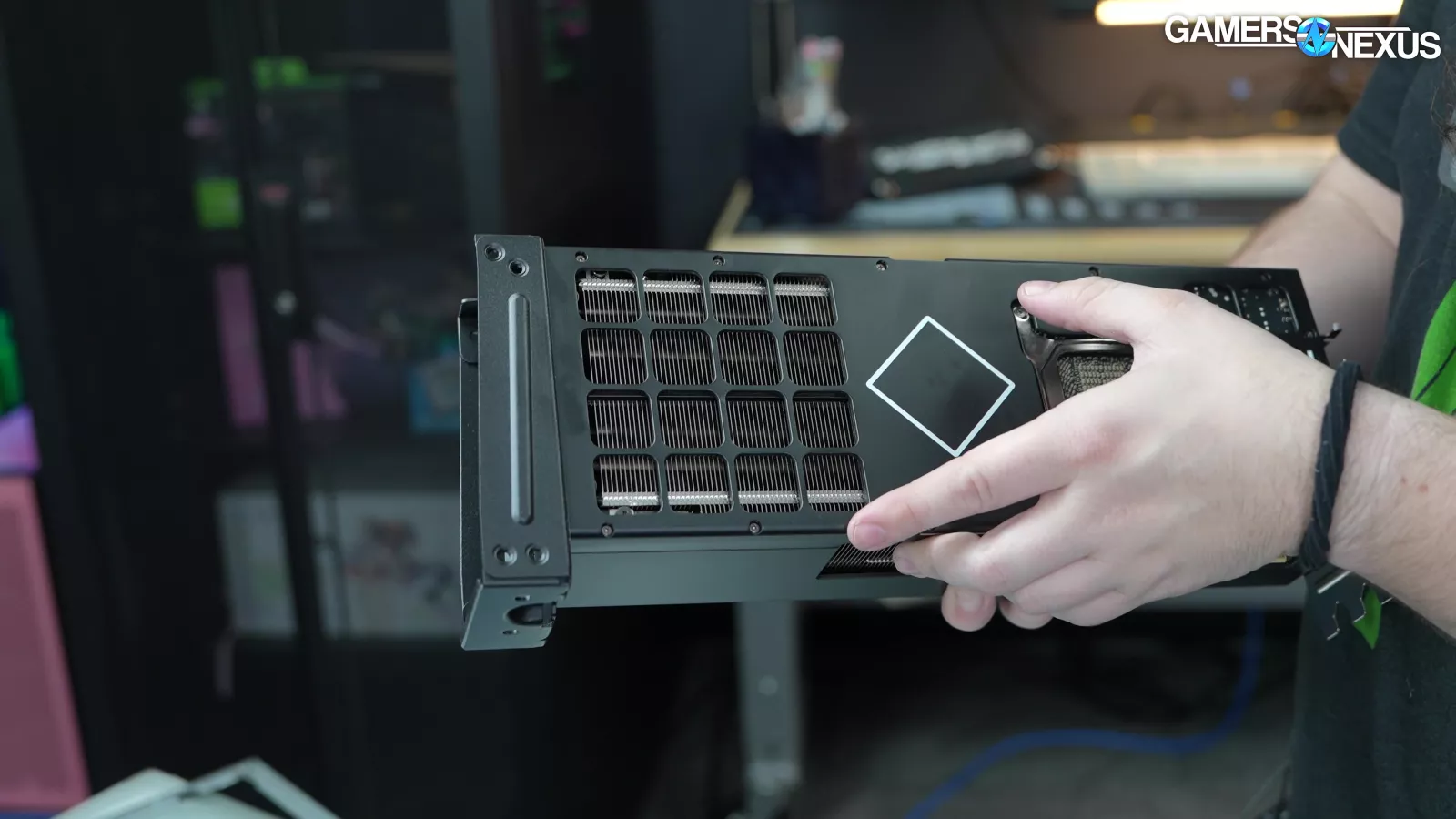

Next, we moved onto pulling out the video card, which was contained within a plastic shroud that was incredibly sturdy. There was also a screwable steel bracket, which allows HP to ship the PC with the video card pre-installed without any protective internal packing that are commonly seen in other SI builds.

With its shroud, the GPU ends up being a 3-slot card.

Looking at the video card out of the case, the shroud doesn’t cover most of the fins on the side, but it does cover some fins, which prevents air from escaping.

The good news is that there is a hole in the back so air can get out again, which should actually be aided by the fact that the shroud sealed off some of the fins on the card’s side. This might explain why the GPU performed okay.

The card is ventilated on the back and the shroud is reasonably well put together. It’s probably the best thing HP has done in the computer.

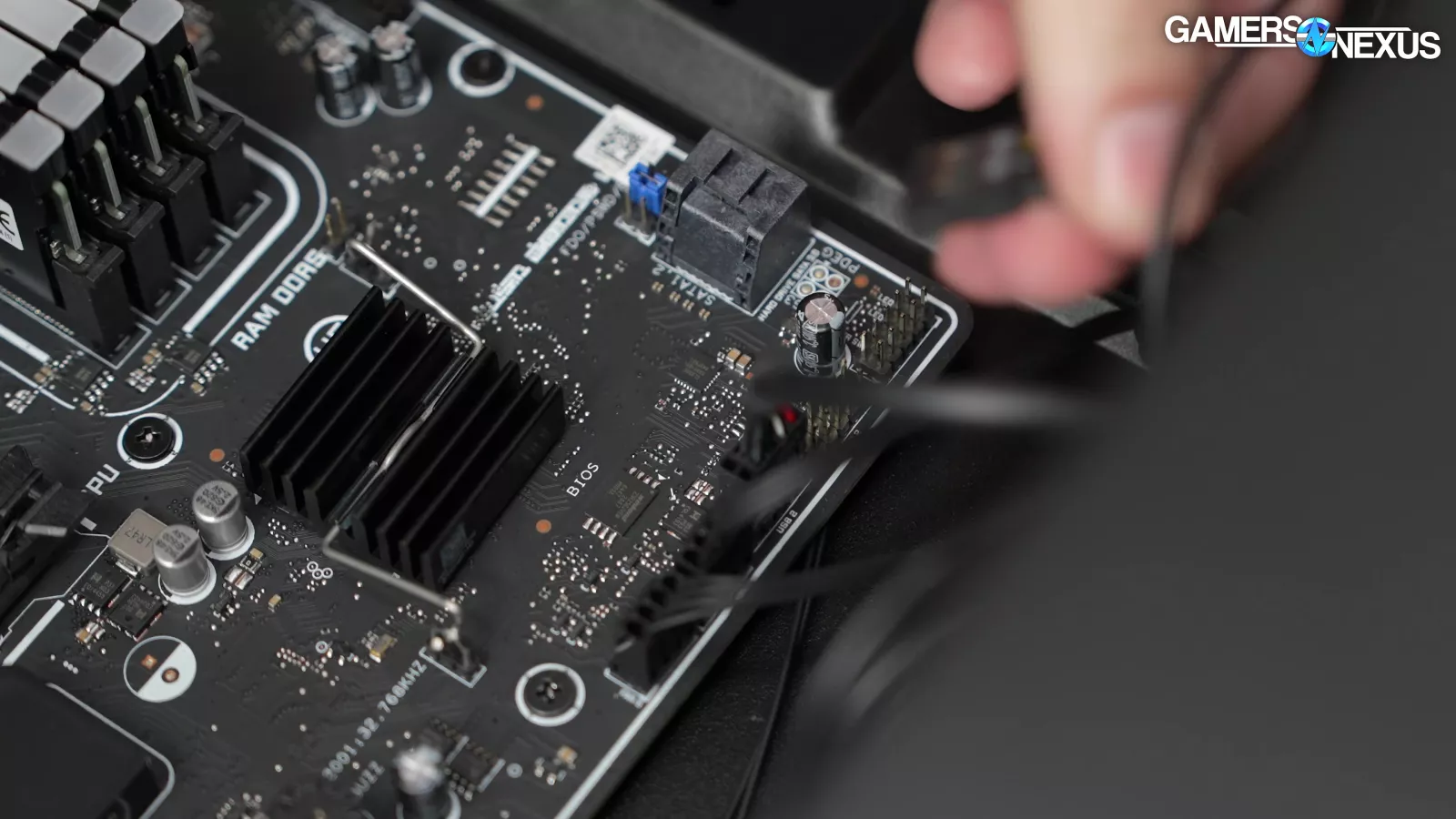

Continuing our tear-down, we started pulling cables from the motherboard and removed the PC’s wireless card.

Doing our tear-down, we noticed how small the chipset heat sink is.

The heat sink on the VRM was really nice, on the other hand. They are really tall and our unit had good thermal pad contact on the bottom. The heat pipe connecting the 2 sides is also a nice touch.

Removing the SSD, we noticed that it was very slightly bowed, but it isn’t bad and doesn’t concern us.

Removing the back side panel, we noticed a plate that said “required for VRM cooling,” which we proceeded to take off. This exposed some thermal pads for the VRM mosfets, which is a nice touch, but it’s hard to appreciate when the CPU runs up to 105 degrees Celsius.

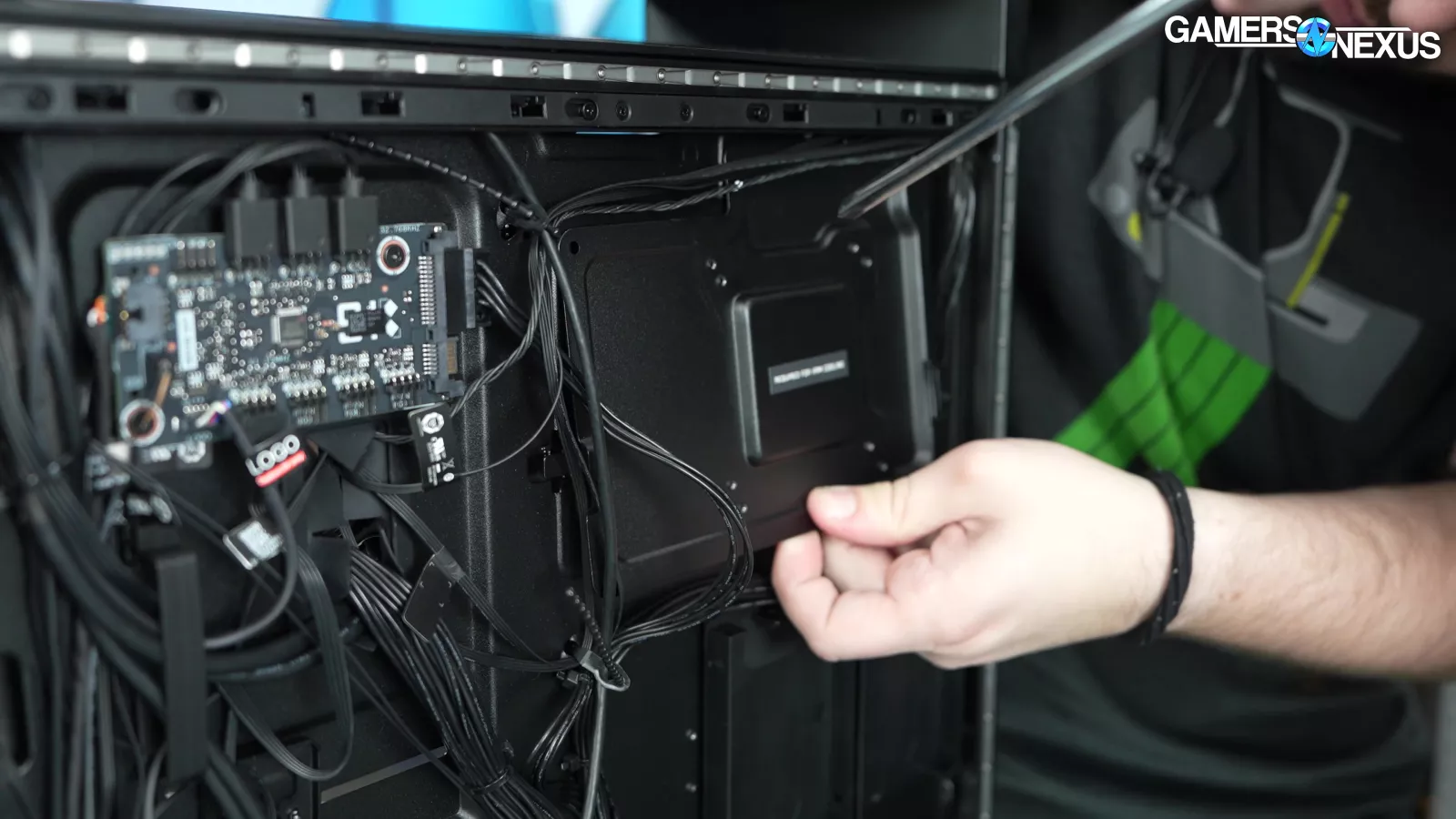

Taking a closer look at the backside, there’s 2x 2.5-inch SSD slots that are not pre-wired (some companies do that). In terms of cable management, it was done to what we would call the minimum degree. Really, it’s a mess, but it’s fully covered. This is where the smaller system integrators do a better job.

Benchmarks

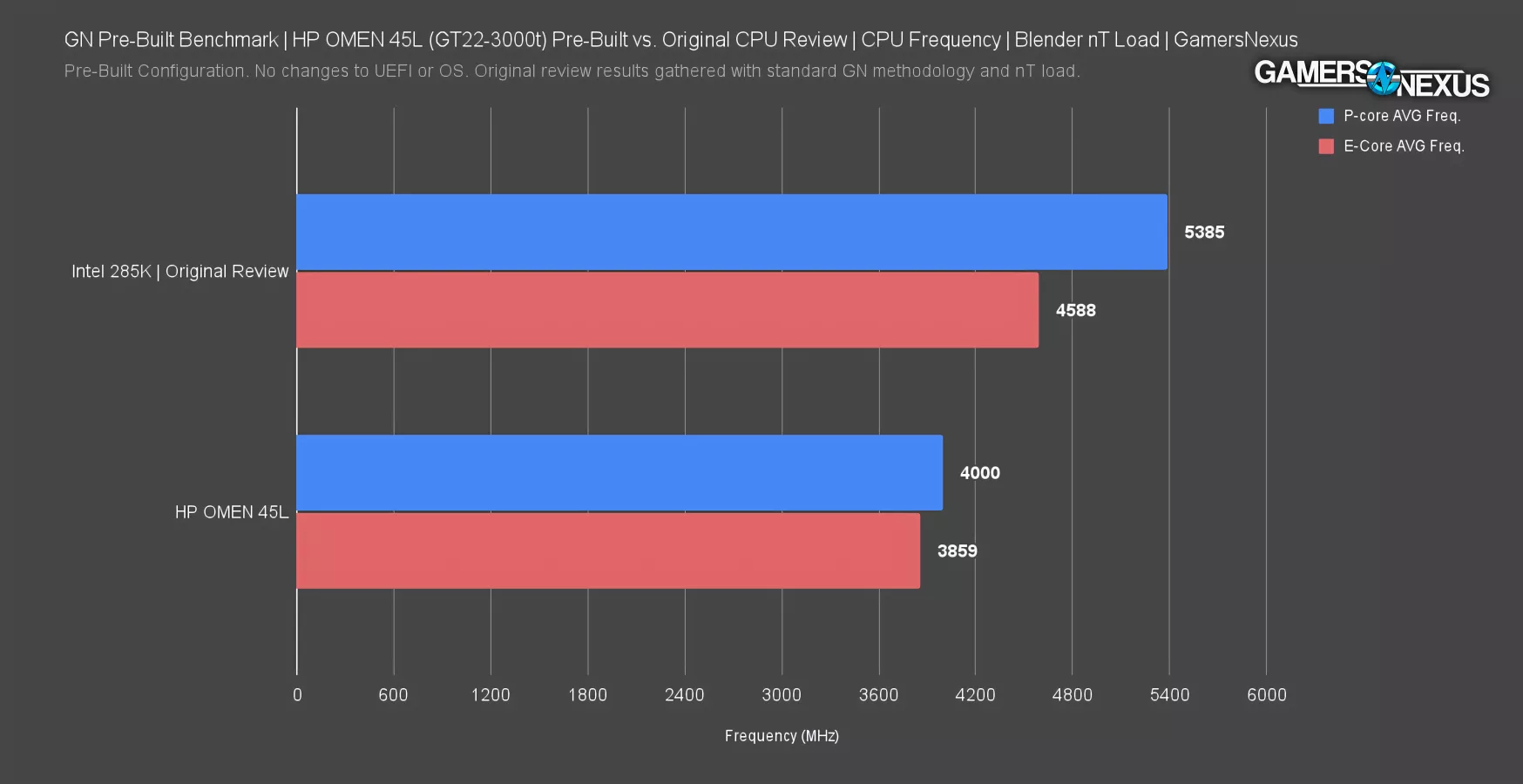

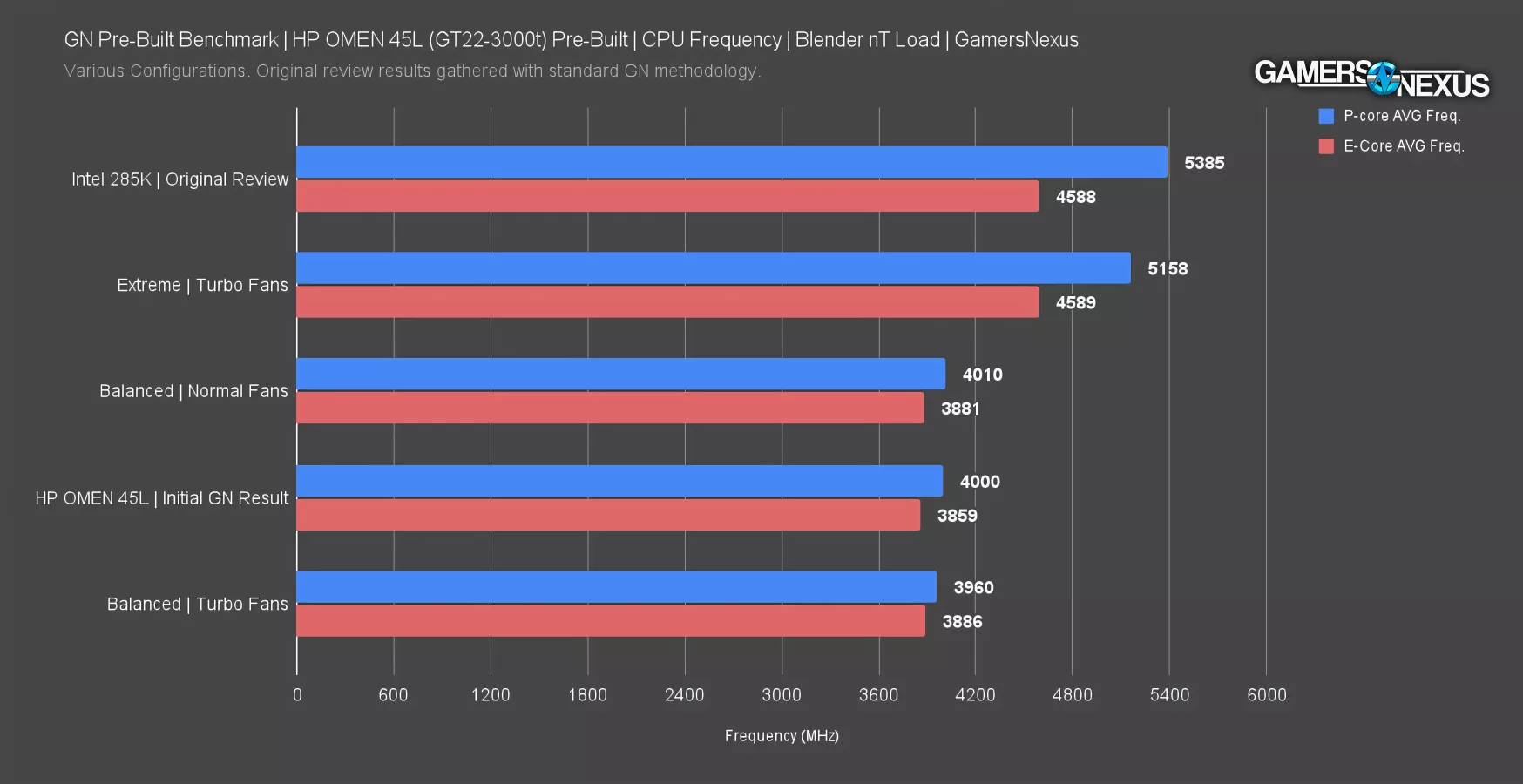

CPU Frequency vs. Original CPU Review - Bar Chart

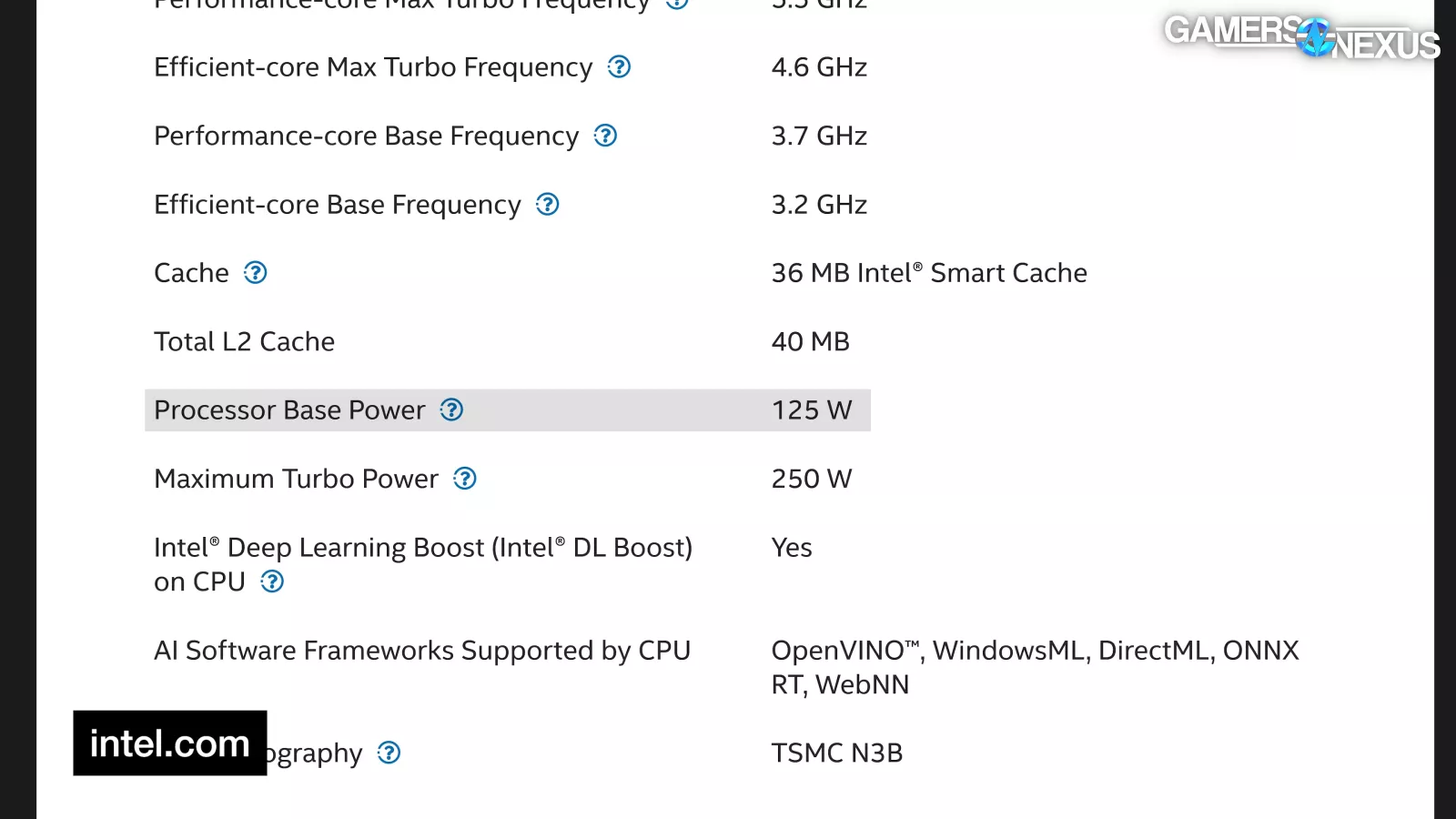

We’ll start with the incomprehensibly bad part: The 285K’s all P-core frequency is 4GHz here. The last time we saw an Intel all-core frequency of 4.0 GHz, it was in some tests on the i7-4790K from 2014. HP has managed to send this CPU back to the dark ages, before the first Great Intel Extinction event.

That 4GHz result has the CPU a staggering 1385MHz slower compared to the 285K in our review testing. Even the E-cores suffered a 729MHz loss.

This is the worst divergence from stock performance we’ve ever seen, falling embarrassingly below expectations.

This deserves a deeper look.

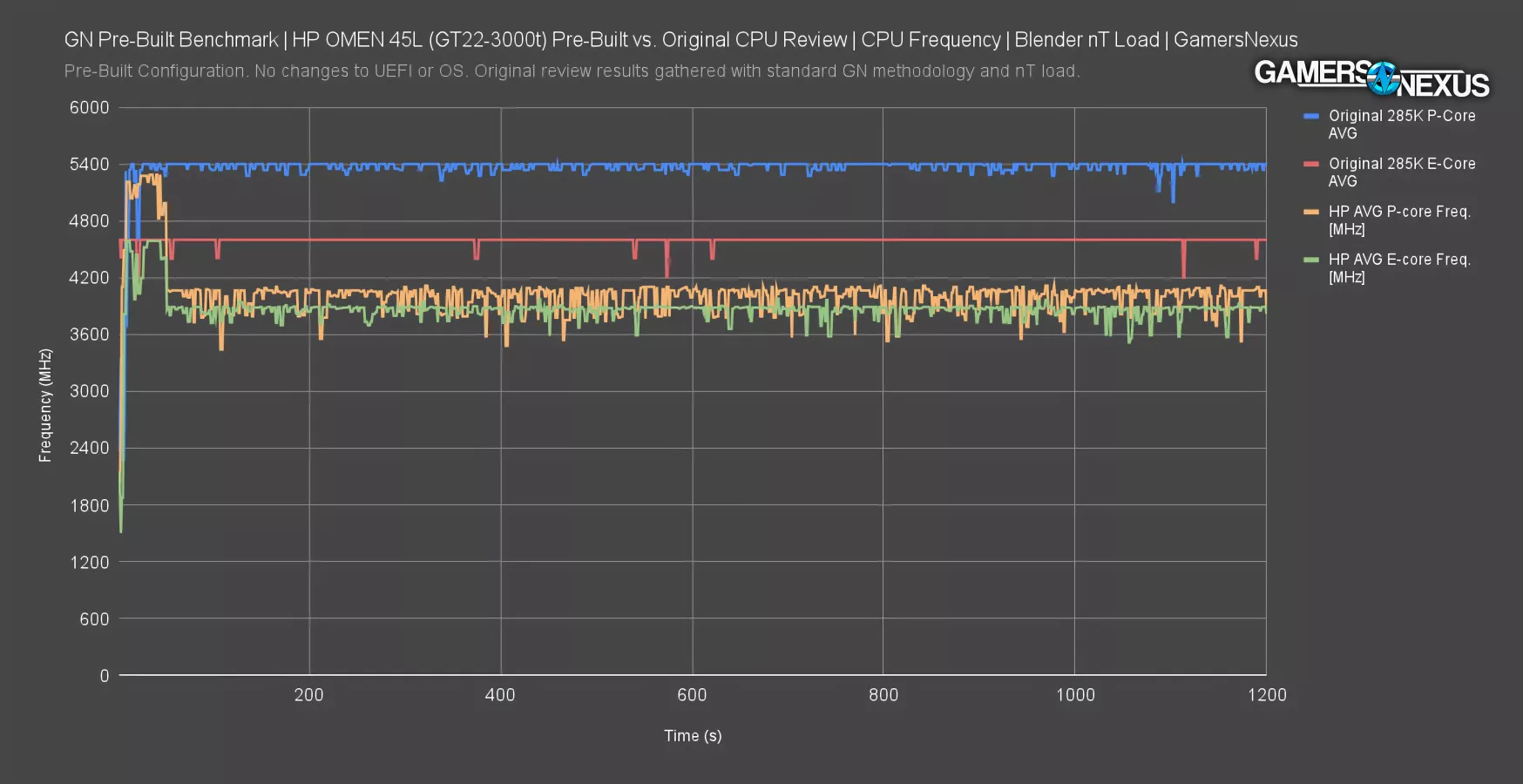

CPU Frequency vs. Original CPU Review - Over Time

This is an over time plot of the same test. The 285K in our original review attempted to hold its P-cores at 5400MHz, with frequent small dips. Its E-cores stayed almost flat at 4600MHz.

In the same test, the 285K in the HP OMEN 45L tried its best to keep up initially, but then got sent back to 2014 to hang out with Devil’s Canyon at around 4GHz by the time it hit the 50 second mark. In this case, 4GHz was just a coincidence for the 285K, as clock behavior was unstable.

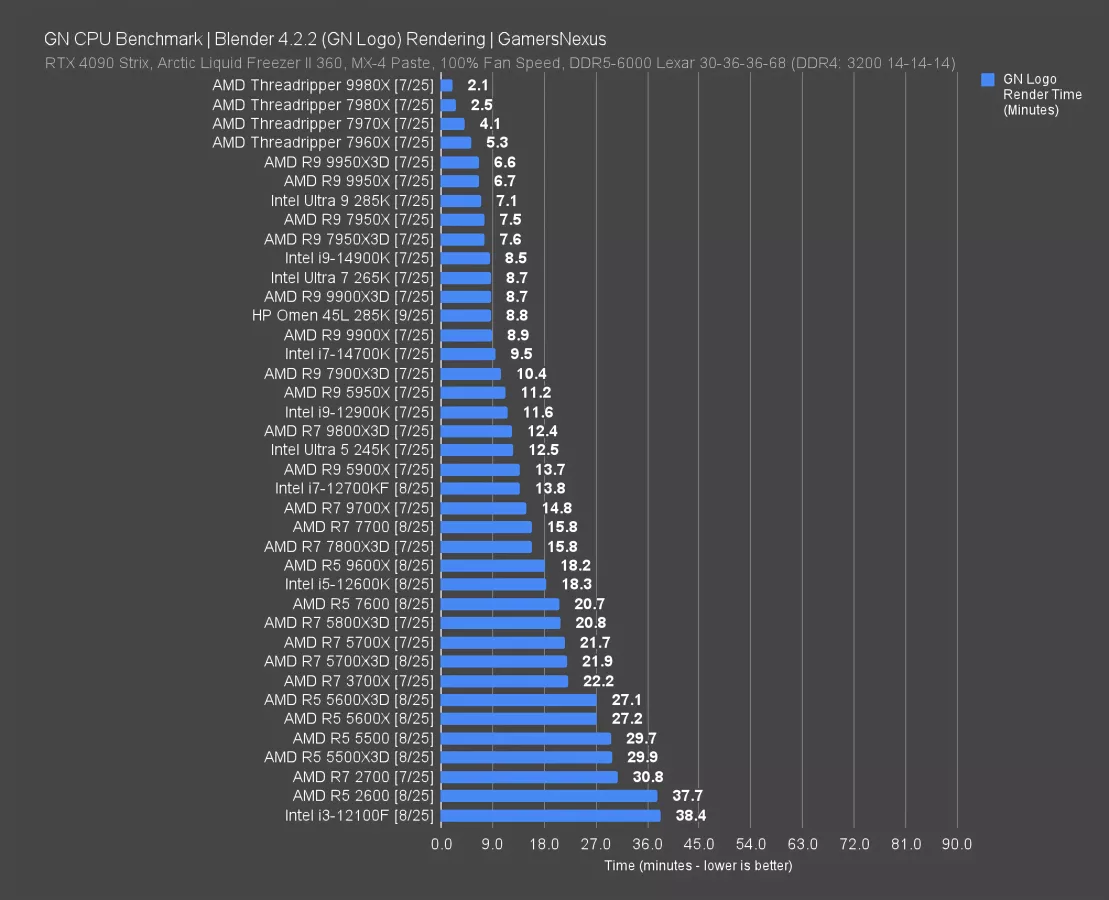

Blender Rendering Performance

We ran the Omen build through our standardized Blender CPU rendering benchmark to see how much performance was lost. The 285K requires 7.1 minutes to complete the render in our normal testing, with the Omen version of the 285K requiring 8.8 minutes. This is such a huge reduction in performance that HP has managed to make it worse than a 265K (read our review) despite having 4 more threads. It’s hardly better than a 14700K (read our review). This is impressively bad and means that you’re paying at least the difference of a 265K to a 285K, yet getting 265K performance.

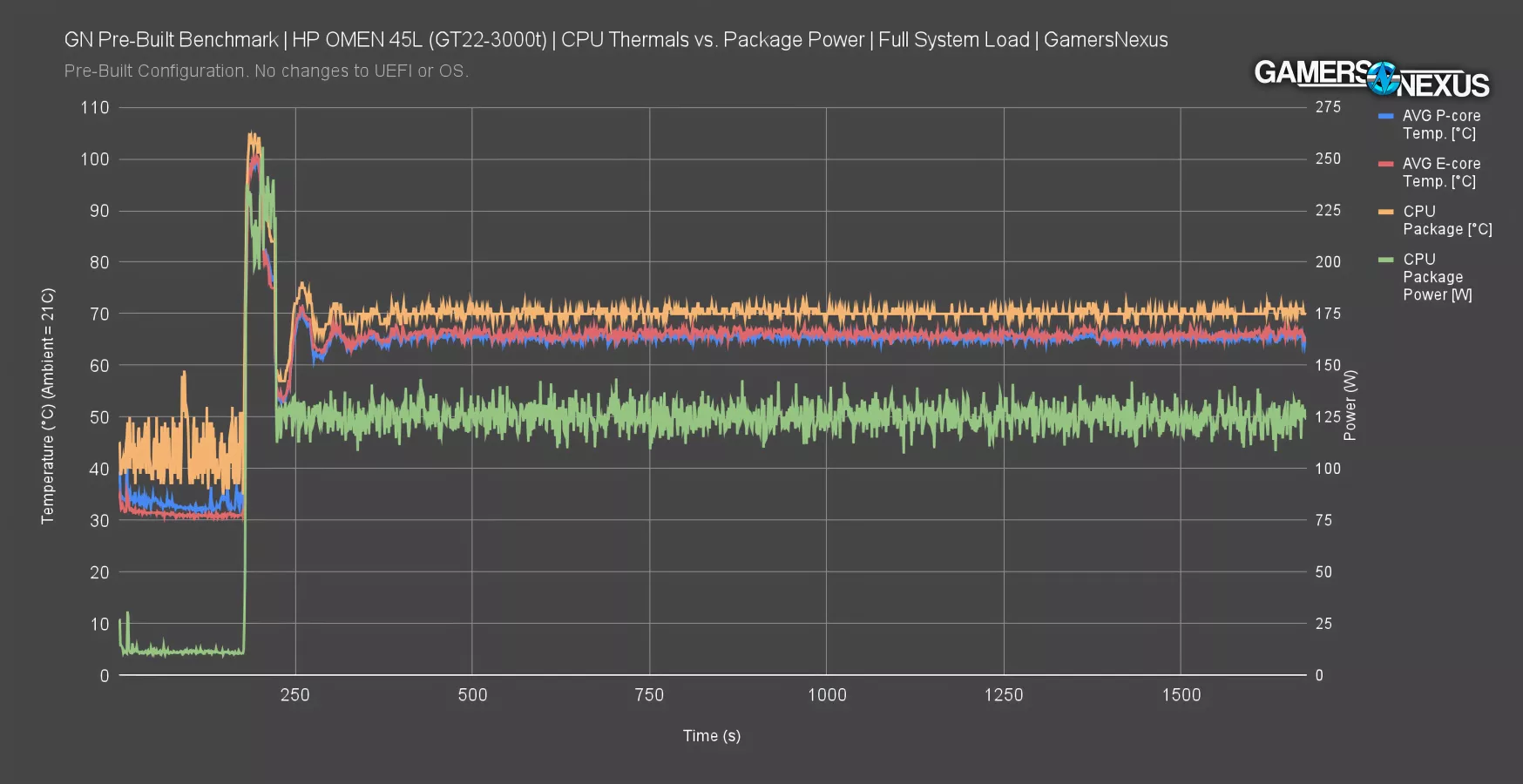

Thermals - CPU - Over Time

Next is CPU thermals. We’re excited to see how the “CRYO” chamber holds up since CRYO means frozen.

HP’s near-literal dumpster fire of a PC caused us to alter our chart template in order to convey the sheer thermal intensity. Our charts for temperature normally stop at 100 degrees, but we had to increase the chart scale to fit HP’s impressively bad result.

Within seconds of the CPU load starting, P- & E-cores spiked over 100 degrees Celsius. Immediately after, the temperatures crash downward to the mid 50s, climb to about 70, and continue on like a diminishing wave for a few cycles. Following that, temperatures stabilize to the mid 60s.

We haven’t seen thermals like this since pre-built manufacturers were screwing up Intel’s power limits.

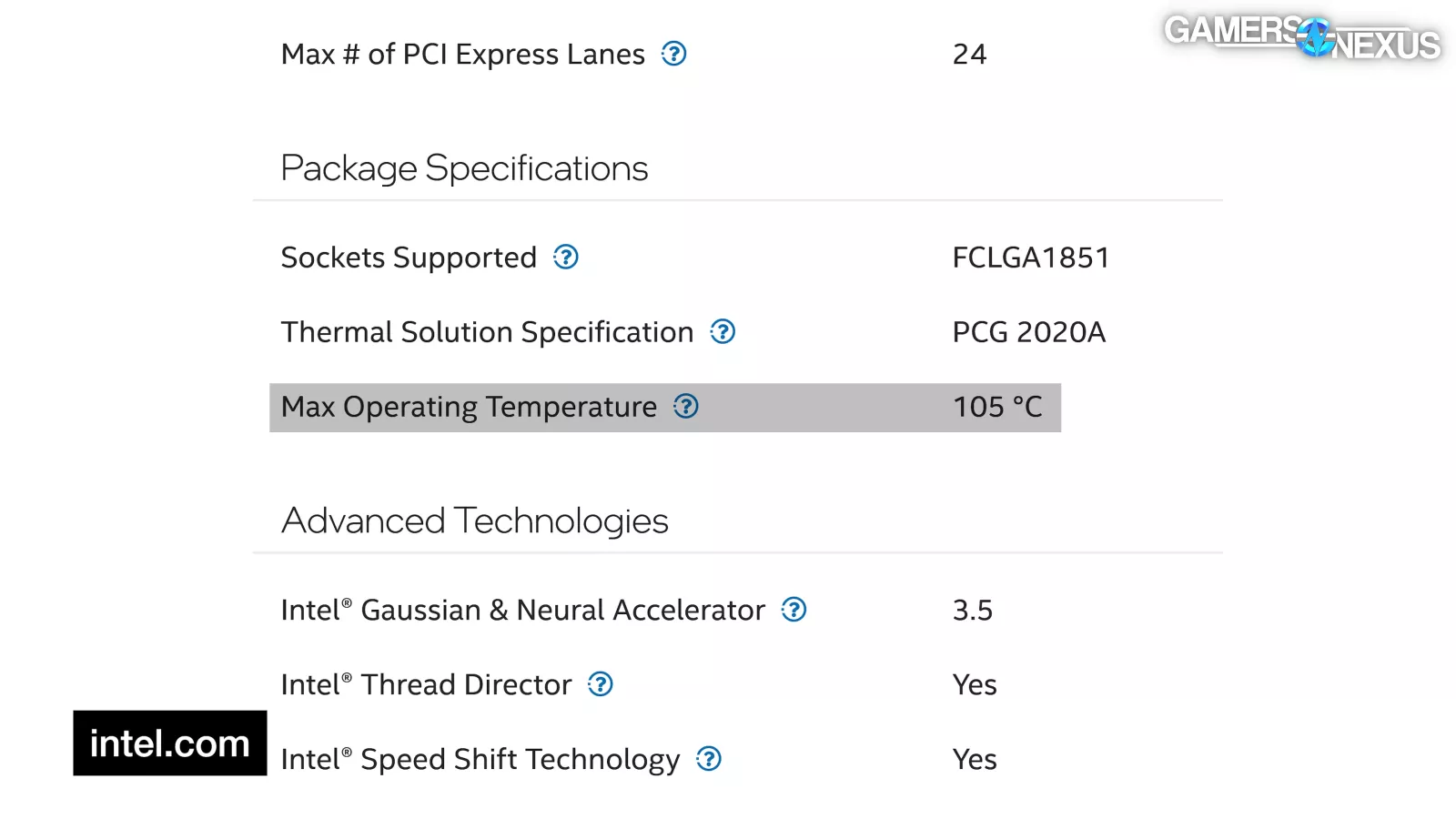

Plotting the CPU Package value shows just how bad it got, reaching all the way to 105C twice, staying at or above 100C for 20 seconds. The max operating temperature for the 285K is 105C, so it was not only thermal throttling, but on the verge of tripping PROCHOT and shutting down. CPU Package temperature then predictably sat above the AVG for the duration of the test.

Finally, adding CPU Package Power explains the temperature drop. It starts very low at idle, jumps to roughly 225W when the load starts (which is near normal for the 285K), then abruptly falls off a cliff to bounce around the 125W mark from then on. That’s roughly half of what it should be in a heavily parallel workload.

This makes it obvious both why temperatures stabilized and why frequency dropped – something triggered power-limiting behavior, bringing the 285K down to its default 125W “Processor Base Power.” The strange part is that board vendors don’t normally configure Arrow Lake to have an explicit window of time (Tau) to move from a higher to lower power limit. Tau still exists per Intel documentation, but typically goes unused, with PL1 equalling PL2.

HP shouldn’t be kneecapping its CPU like this. Again, this is 2014 levels of performance.

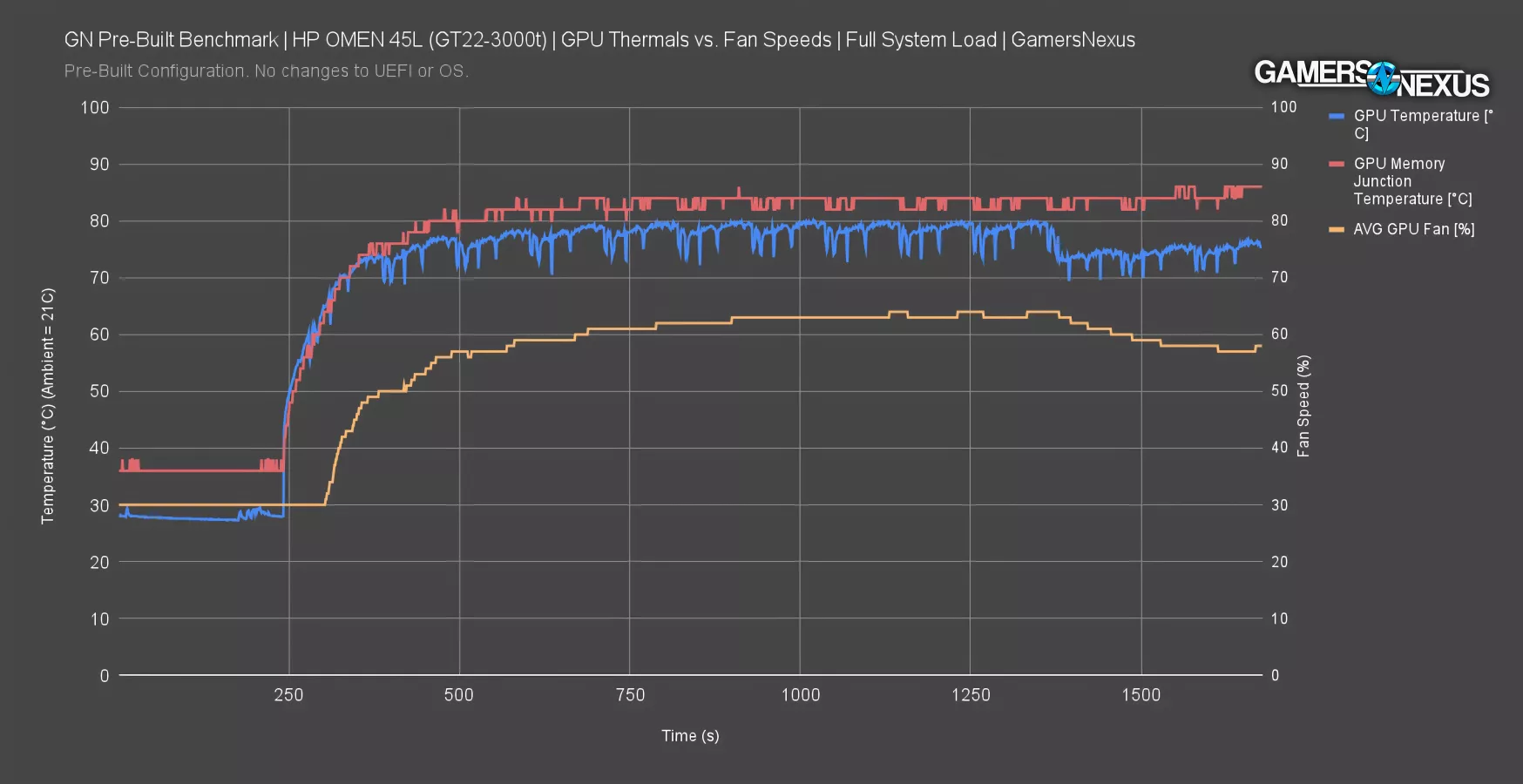

Thermals - GPU - Over Time

The equal-but-opposite reaction to the CPU’s throttling is that the GPU doesn’t have enough work because the CPU can’t provide it, which reflects in the GPU temperature. The 5090 (read our review) briefly cools when it doesn’t have enough work to do, despite being at about 80 degrees for core initially. Temperature drops from about 80 degrees to the mid 70s near the end while GPU fan speed drops, due in part to the case fans speeding up and in part to the low load provided to the GPU by the CPU.

In many cases we’d disqualify a GPU run for being under-loaded, but it’s part of the story this time, and load at steady-state still averaged to 98%.

Memory junction temperature rises above core temperature to roughly 84C, but doesn’t reach the 95-degree-plus extremes of NVIDIA’s Founders Edition design in standalone testing. The fan speed rises to 64%, before trending downward as the case fans engage.

HP’s GPU cooler design seems like the most competent aspect of the entire build, but it’s benefitted by the CPU underprovisioning work.

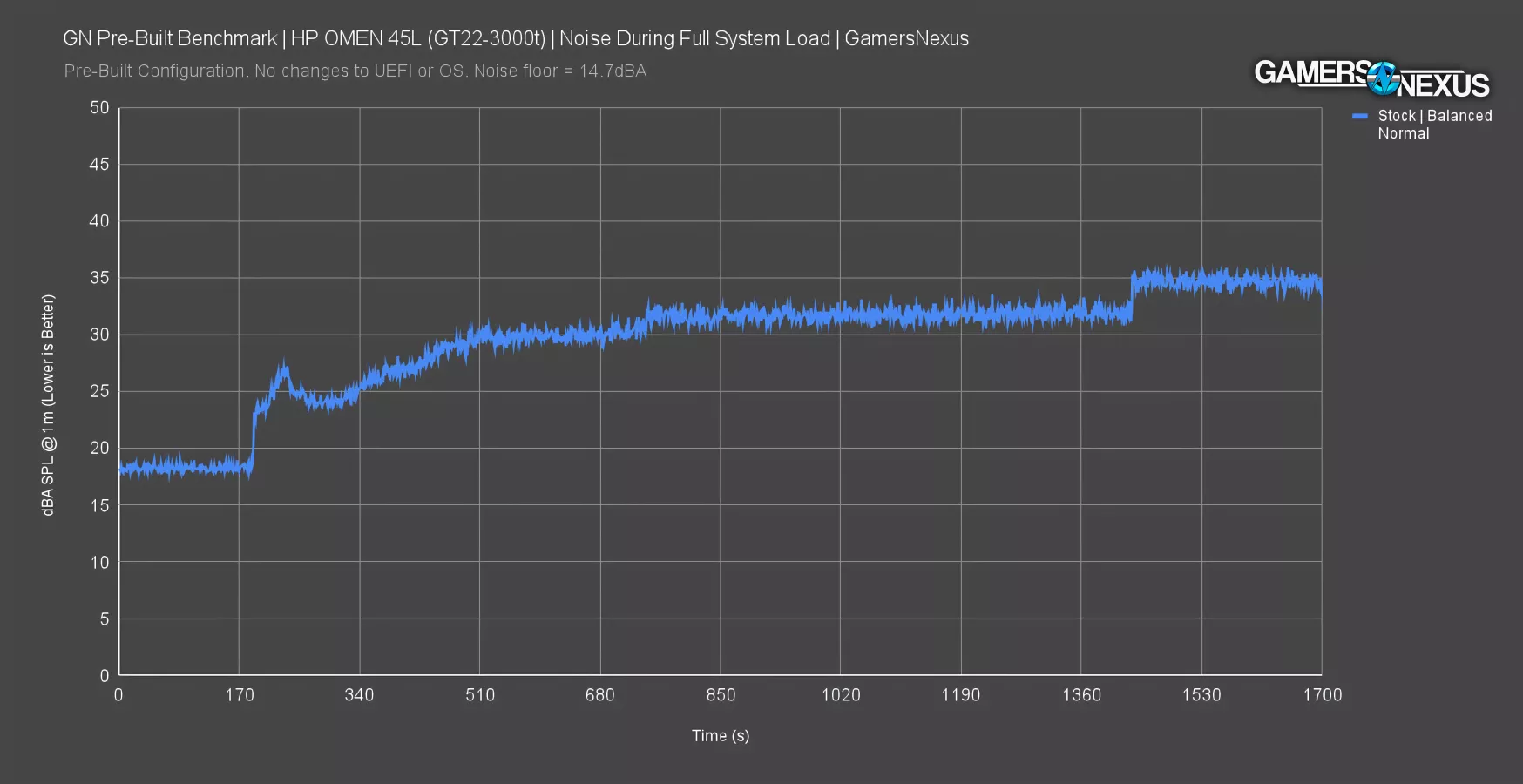

Acoustics - Over Time

Now we move to acoustic testing in our hemi-anechoic chamber that we built for heavily controlled acoustic analysis in an unchanging environment, that way day-to-day noise changes in the office and outside don’t affect our results.

The HP OMEN 45L’s default fan (and therefore noise) profile is very conservative. Idle is phenomenally quiet at about 18.2 dBA in a noise floor of 14.7. That’s functionally inaudible. It’d be a low speed air purifier or something. When the heavy CPU load hits and temperatures soar to 90C or higher, noise output only rises to 26-27 dBA, then immediately ramps down when the CPU becomes power limited.

After that, it’s a slow and steady rise to 30 dBA, followed by a slight step up, then finally another step up to settle at 34.7 dBA average. The ramps are stairstepped in a way that makes sense, if only the rest of the computer did.

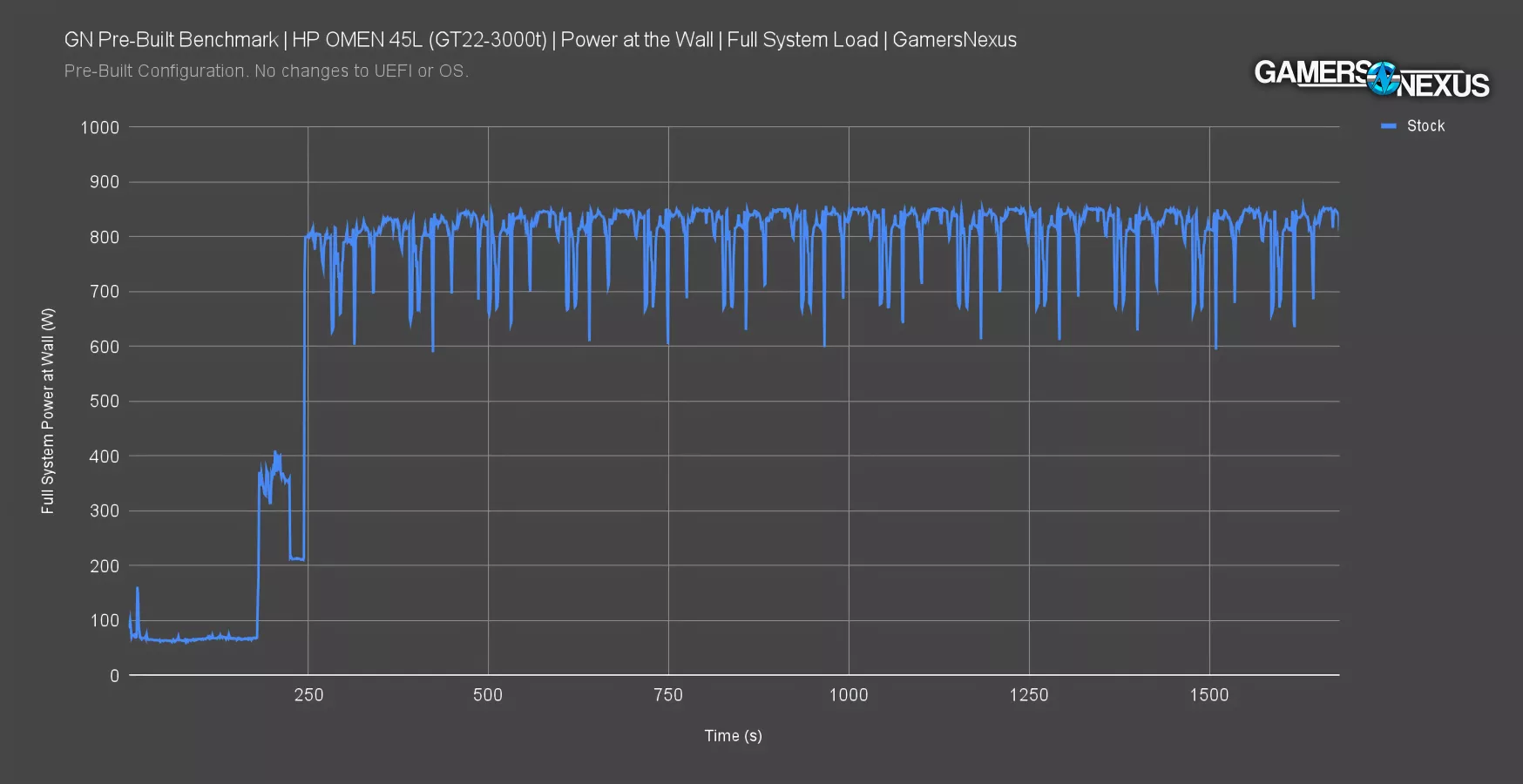

Power Consumption - Full System

Finally, we have full system power consumption at the wall. Full system idle starts in the 60-70W range, jumps around between 300W and 400W, briefly flattens to 212W once the power limit kicks in, then immediately slams to 800W when the GPU load starts on the 5090.

After that, we see the same repetitive dips that we saw on the GPU thermal chart. Again, it’s not what we want to see.

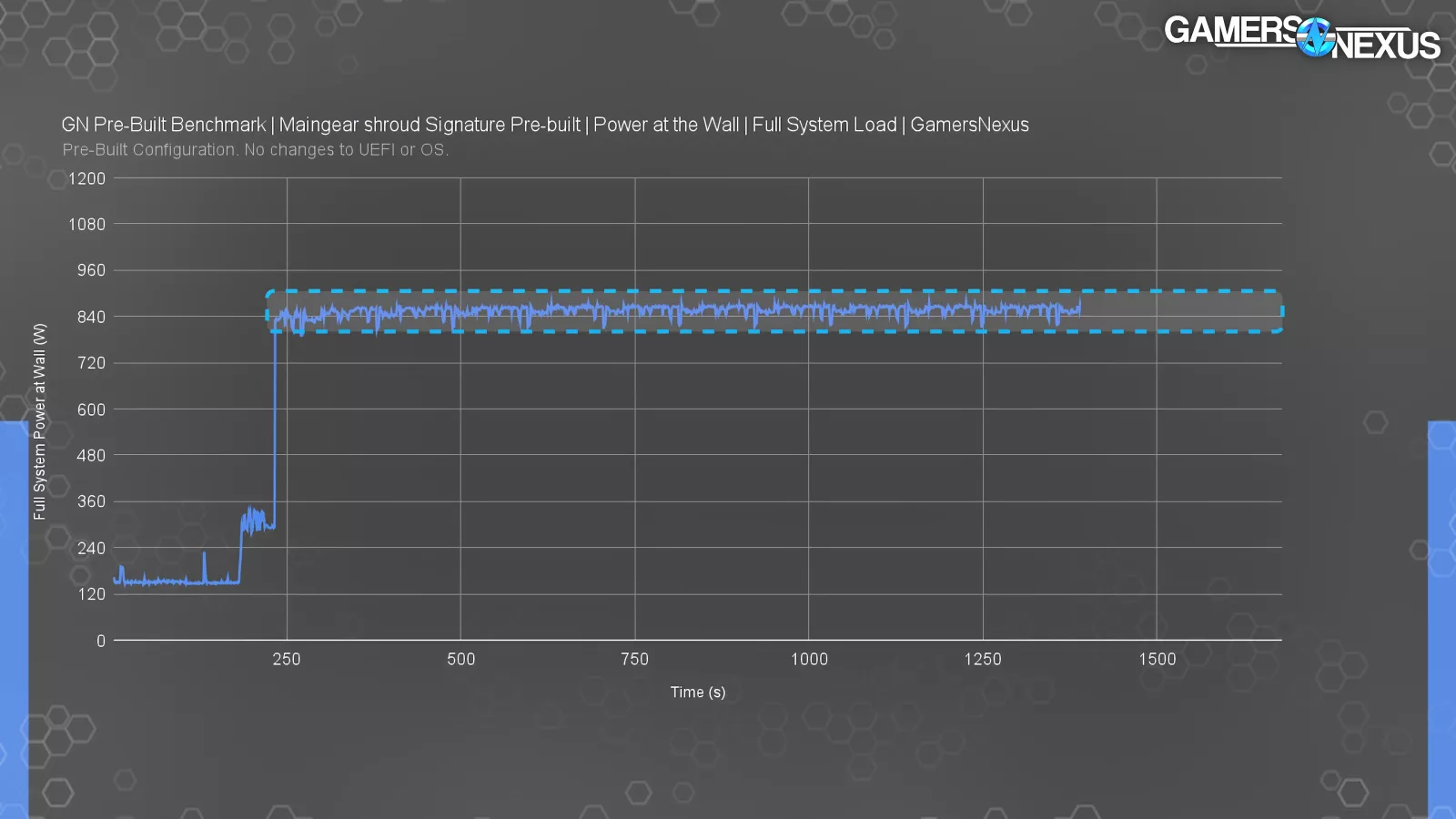

This is what the last 5090-equipped pre-built from Maingear looked like in the same test. Much flatter, which is how it should look.

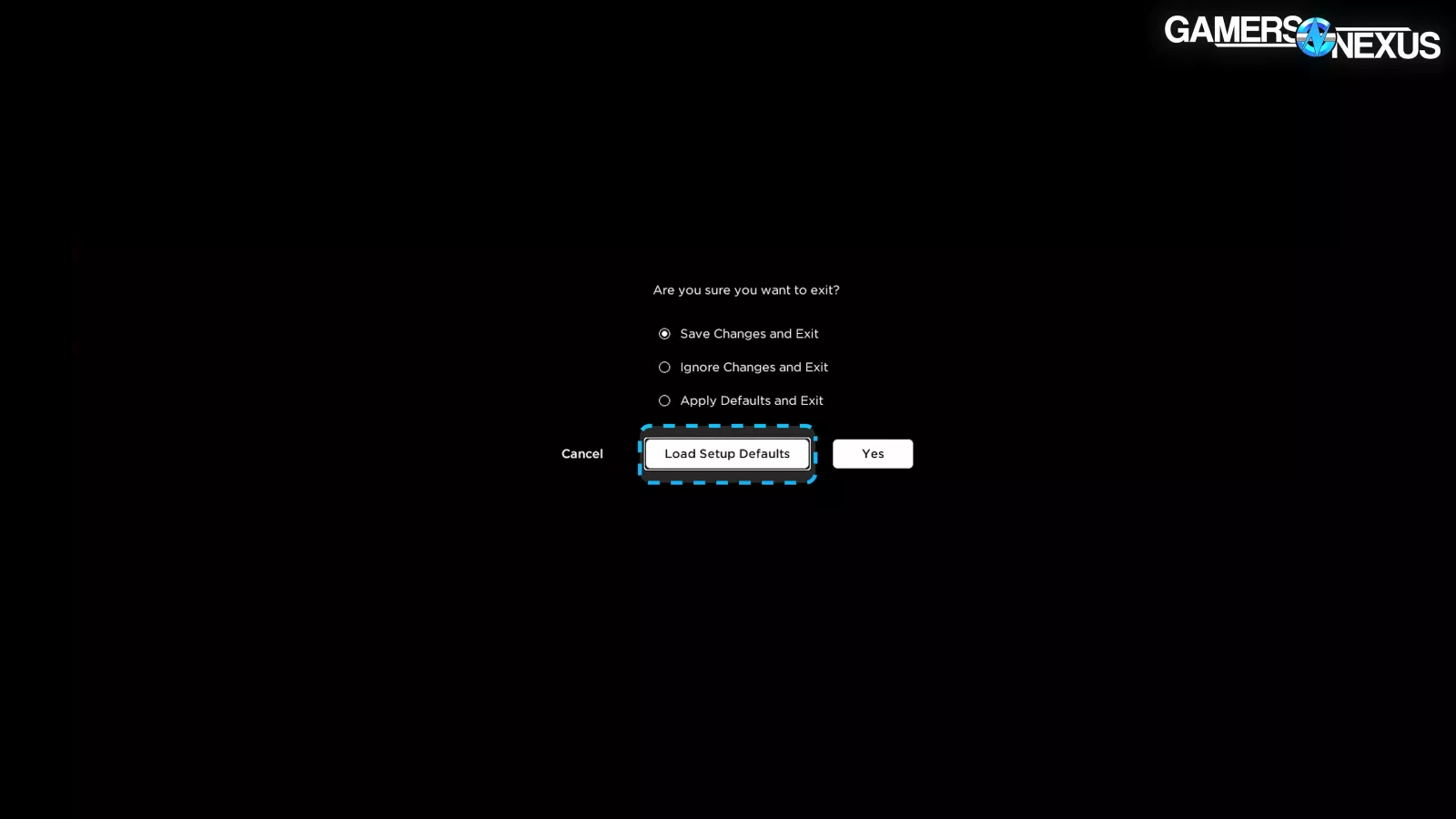

BIOS

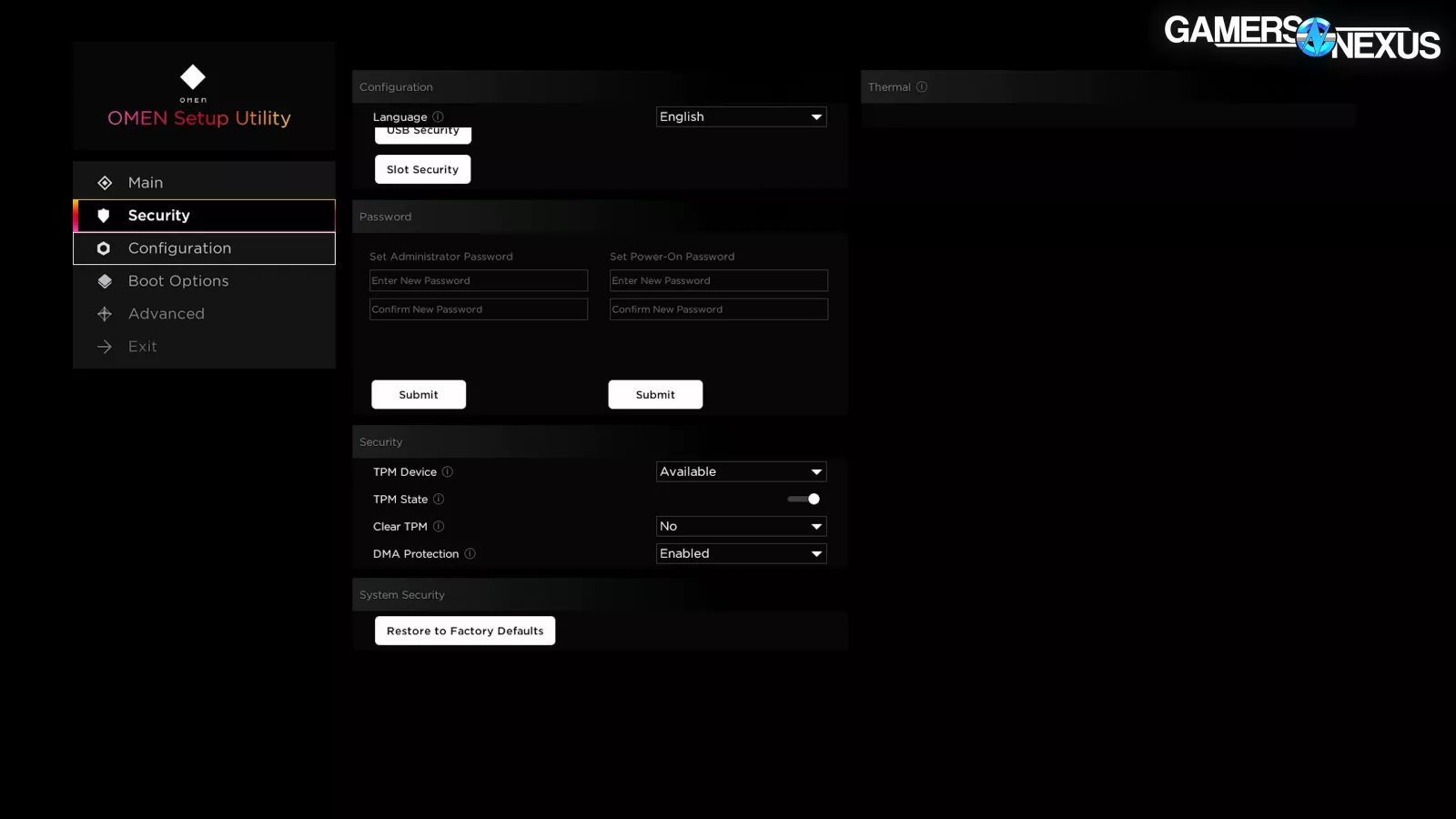

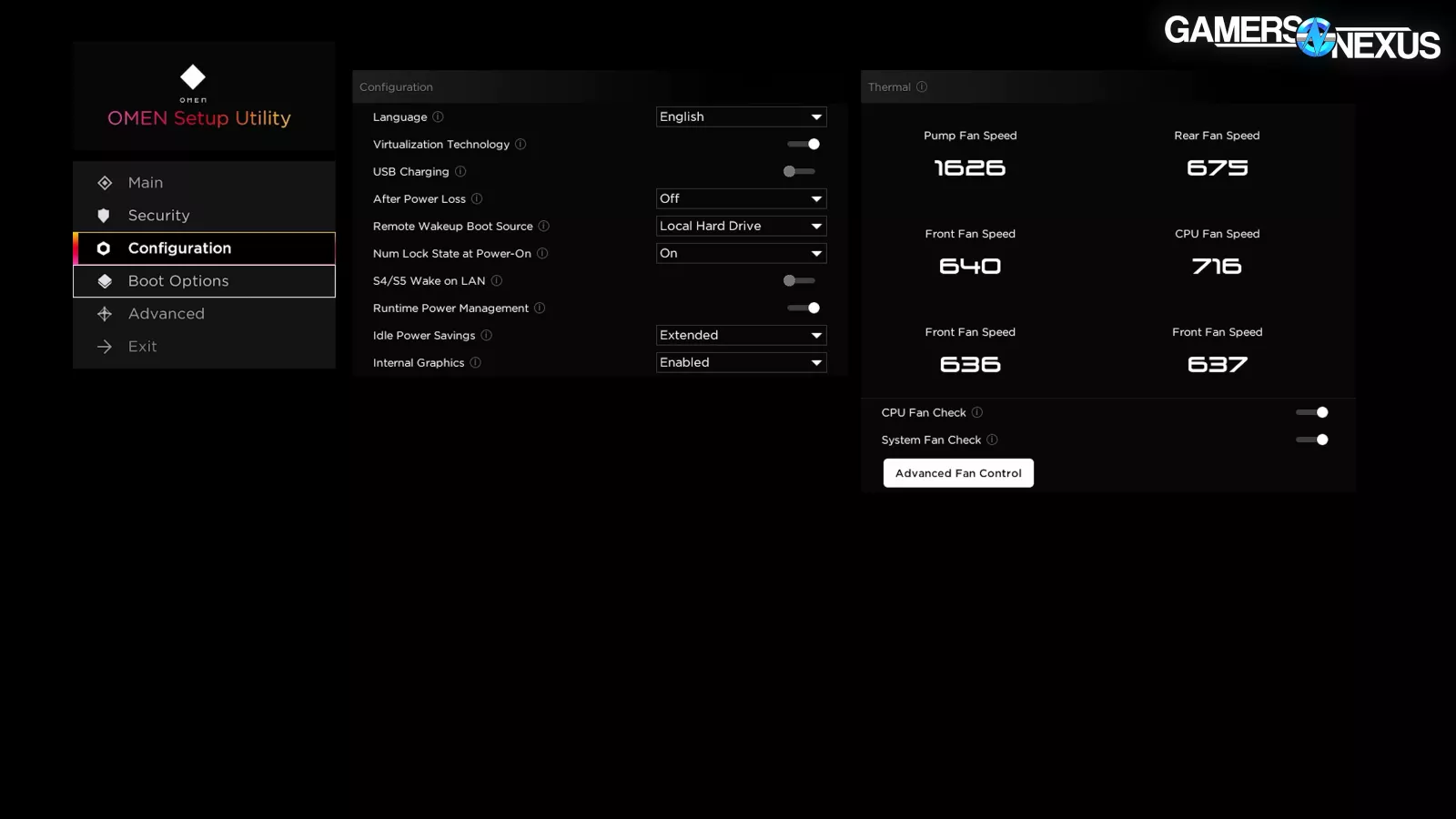

BIOS inspection is next.

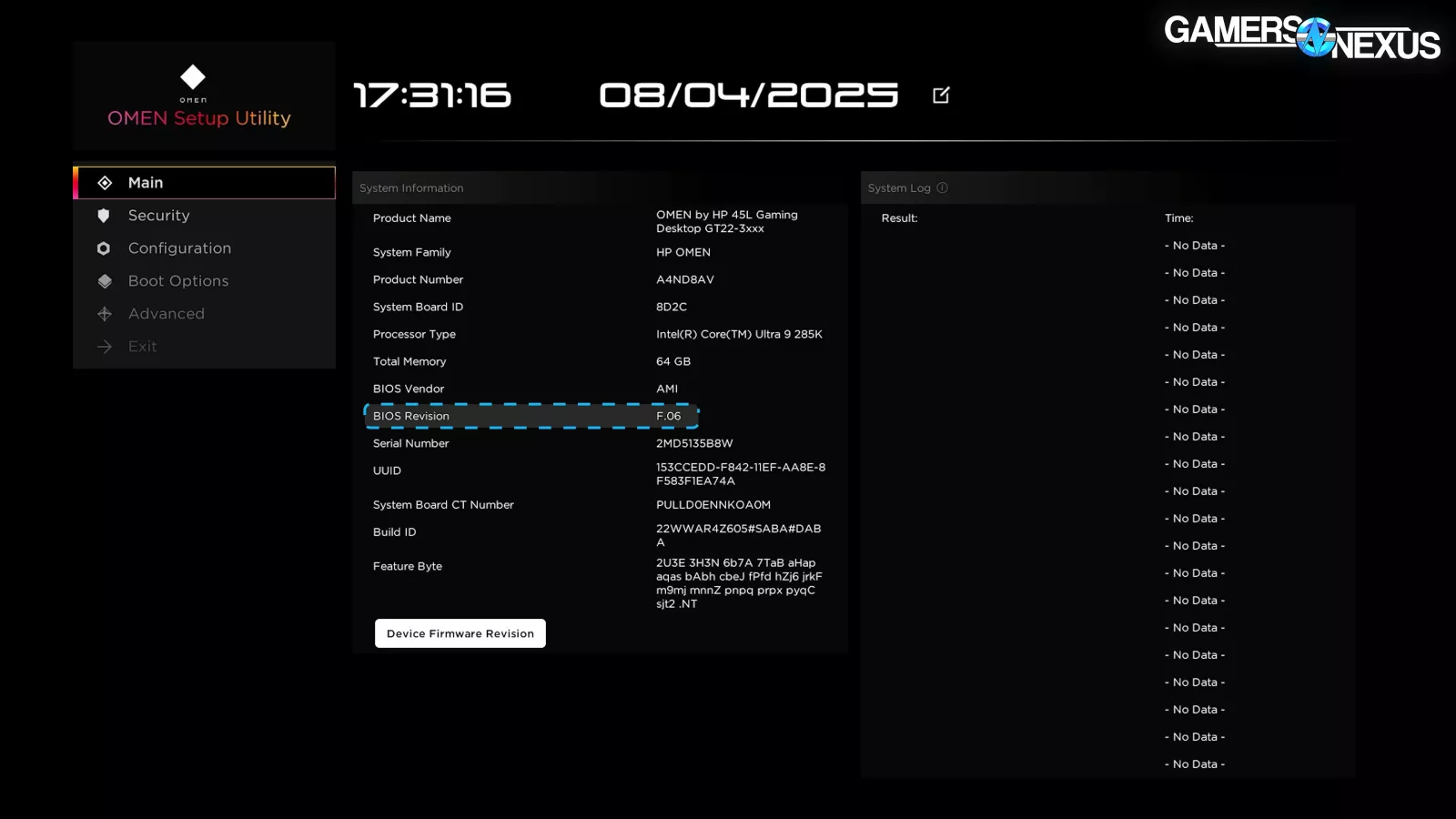

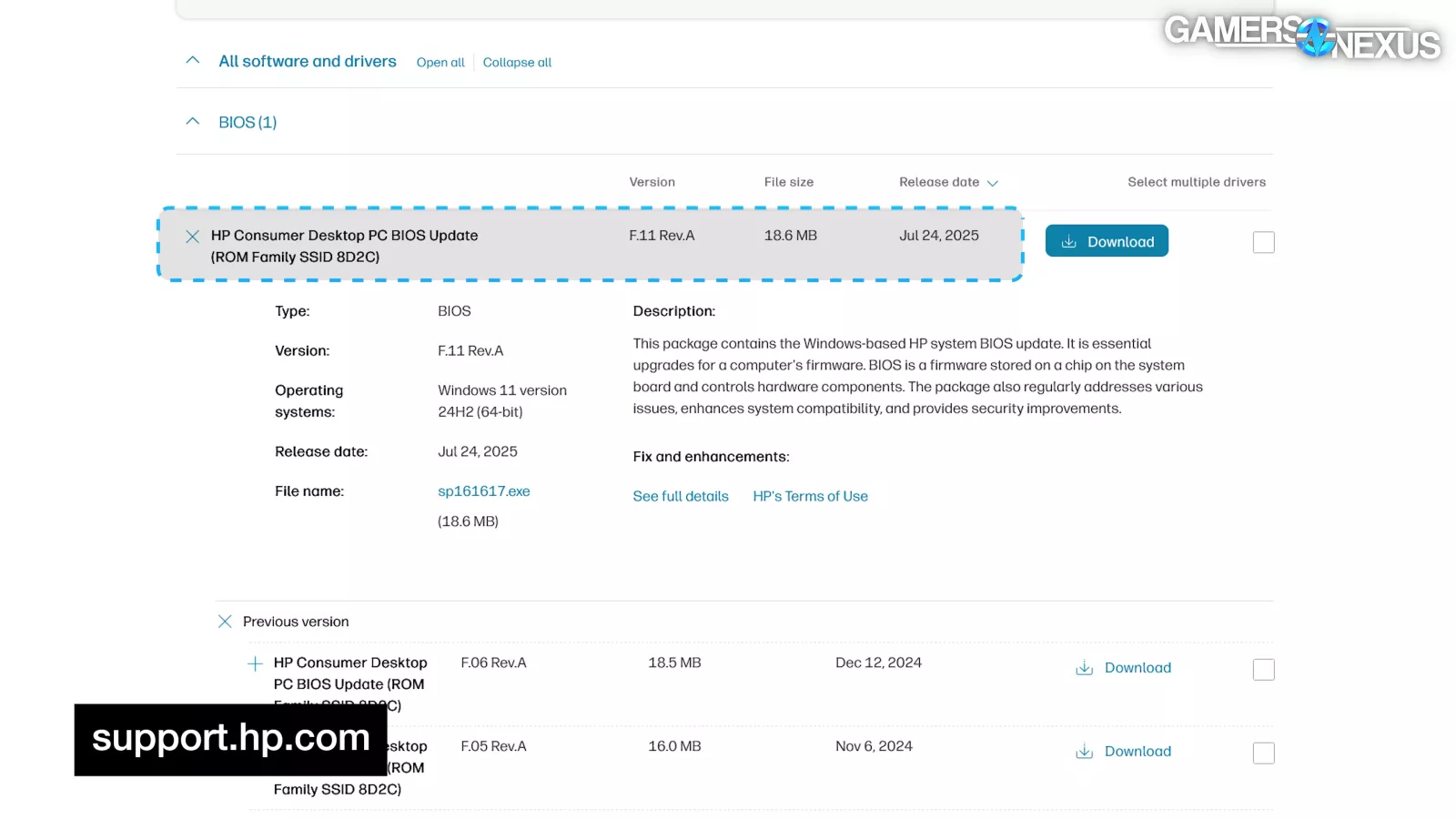

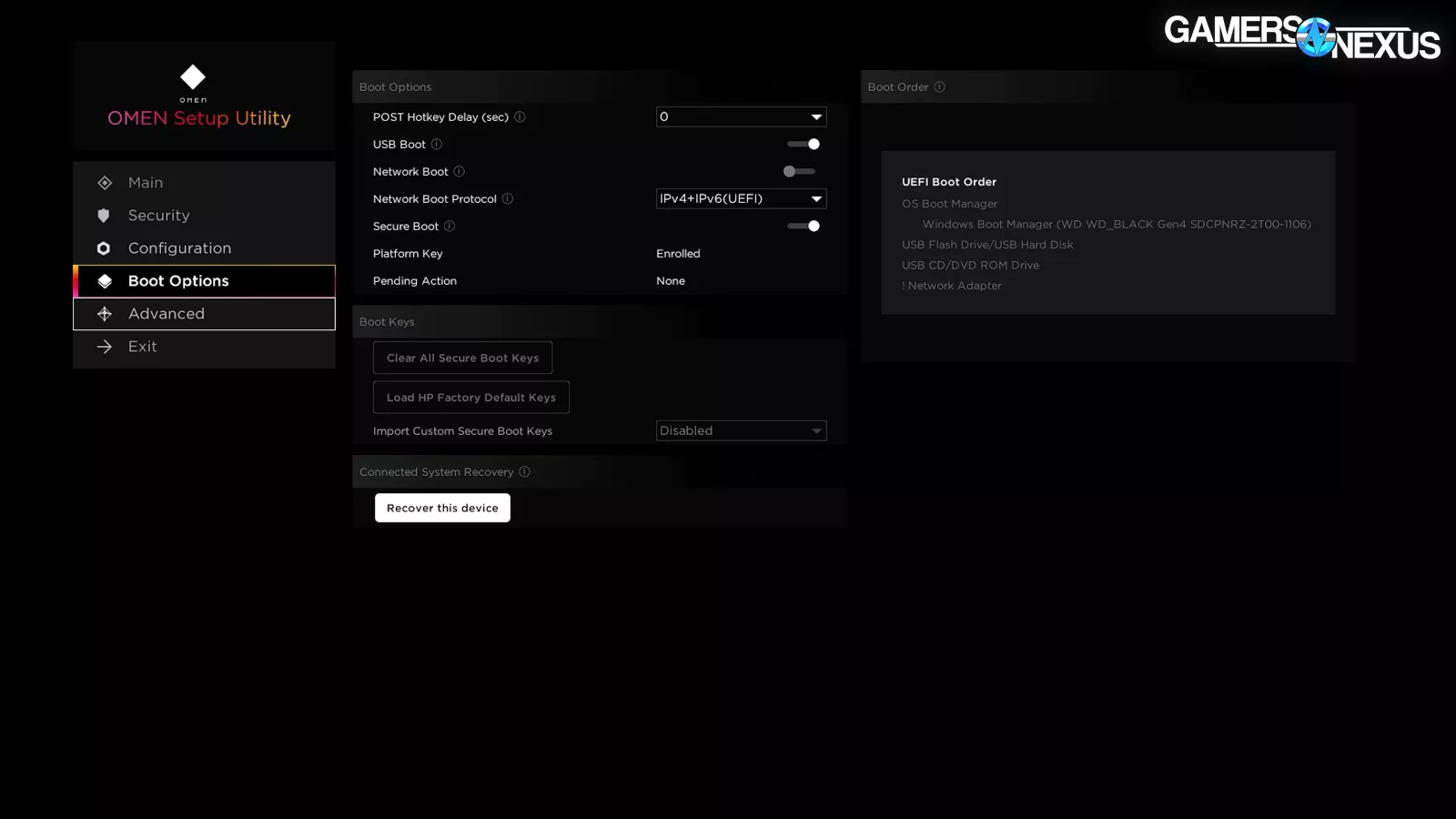

The BIOS for the OMEN 45L is version F.06, released in December 2024. The support page doesn’t show any updates between then and July 2025, but the version number jumping to F.11 makes us think that there were intermediary revisions that have since been removed.

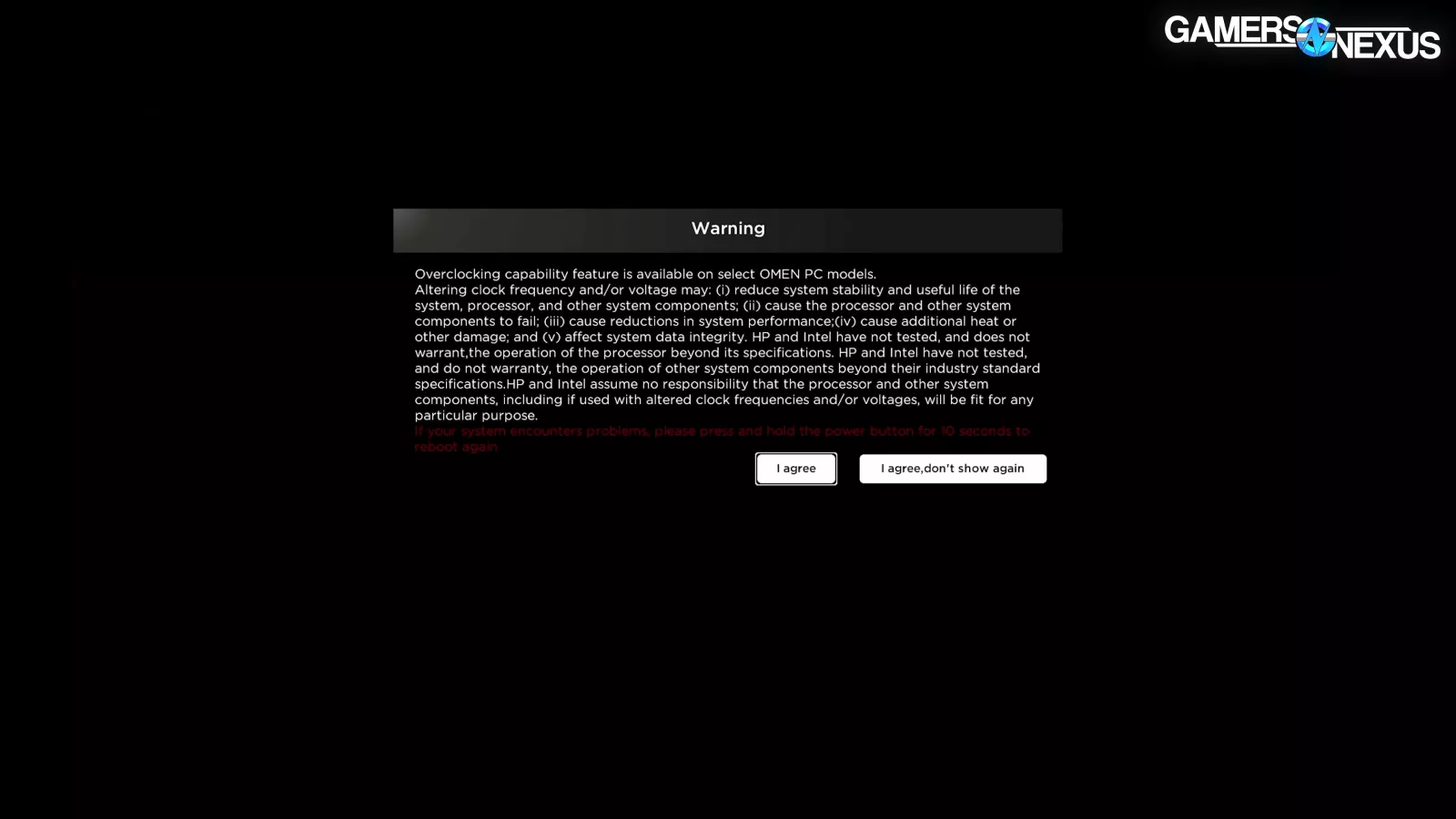

The BIOS itself is stripped-down compared to the full feature sets we’re used to on DIY boards, but enough settings are left exposed to make important tweaks if needed. Opening the Advanced page pops two full screen notifications – one strongly advertising the OMEN Gaming Hub software, and one with a warning about overclocking.

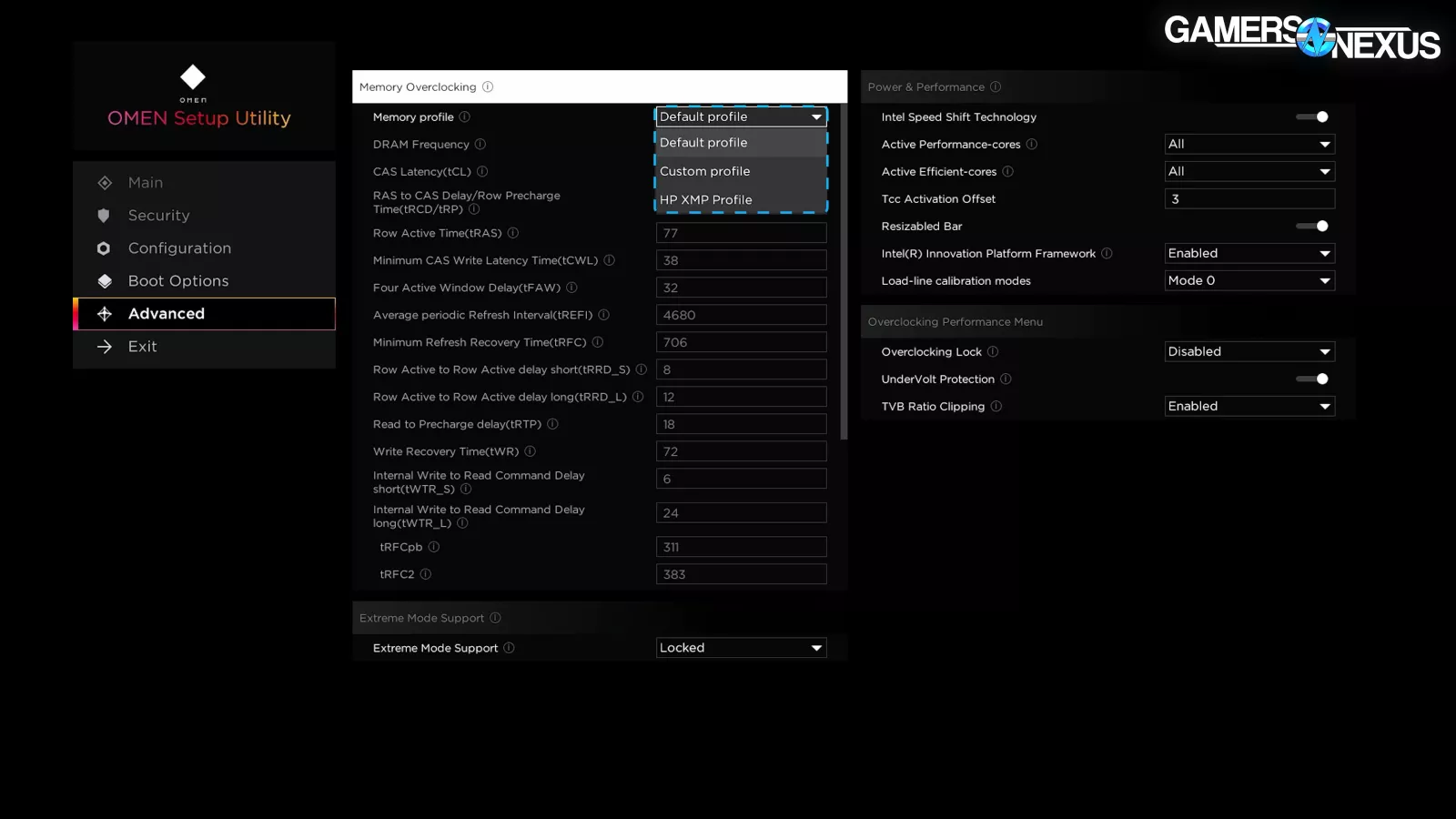

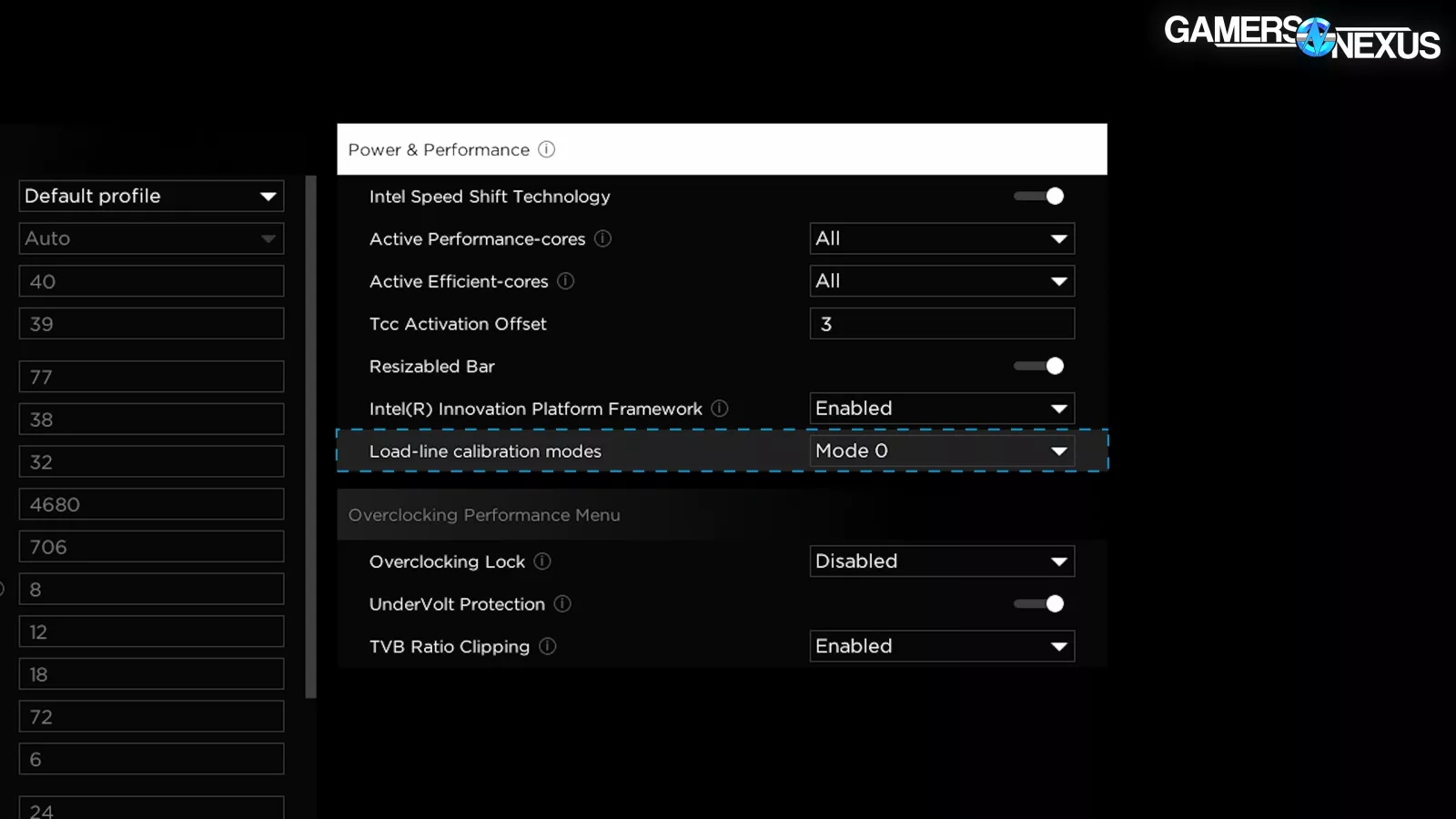

After clicking through, we see that the memory profile is set to default, and not the one that’s literally called “HP XMP Profile.” This is bad enough since that’s a redundant initialism, but it’s made worse by not being enabled. The profile would at least bring the kit up from DDR5-4800 to DDR5-5600.

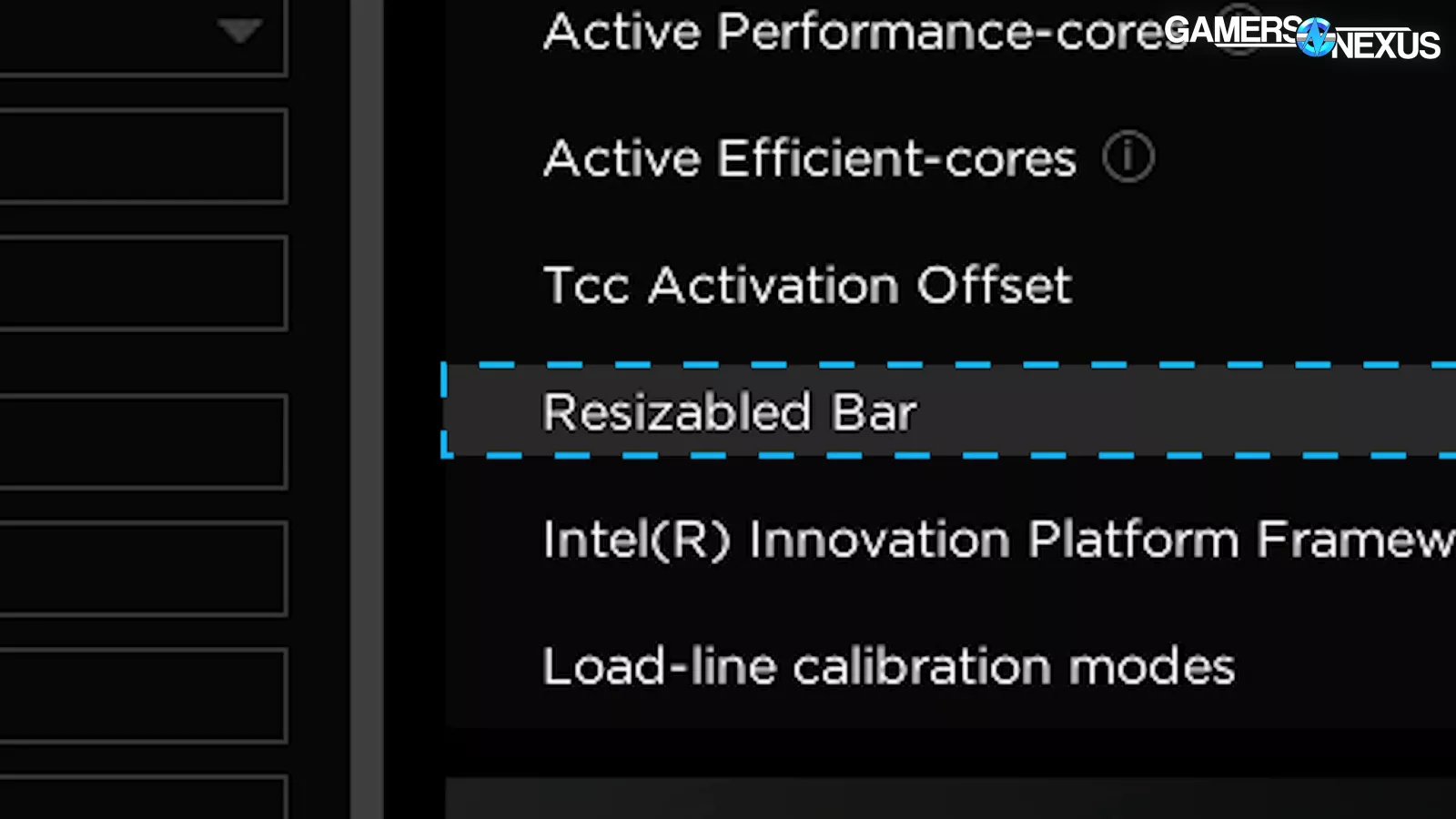

The rest of the advanced page has toggles for LLC modes, an overclocking lock, “Extreme Mode” support, and “Resizabled Bar.” While HP gave us an extra letter ‘D,’ it’s missing a few other things: Power limits aren’t present, so you can disable cores and adjust load-line calibration, but not change PL1 and PL2. You’d have to go to the app for that so HP can harvest your data or something.

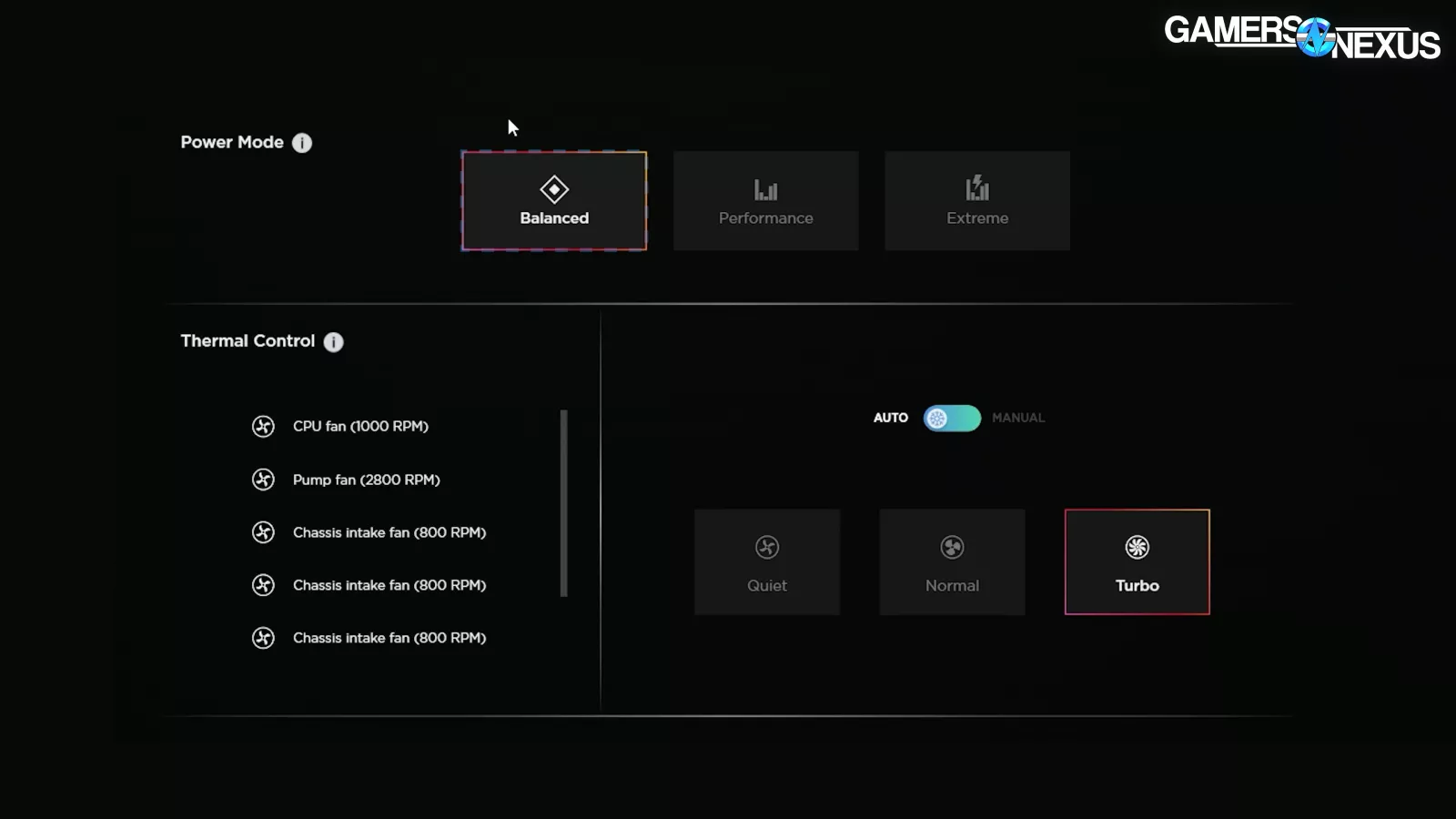

Fan control options were decent. Three pre-set automatic modes (Quiet, Normal, Turbo), and a manual mode that allows for custom curves. We have no complaints here.

As far as we could tell, there was no way to save or load BIOS profiles – just an option to reset to defaults.

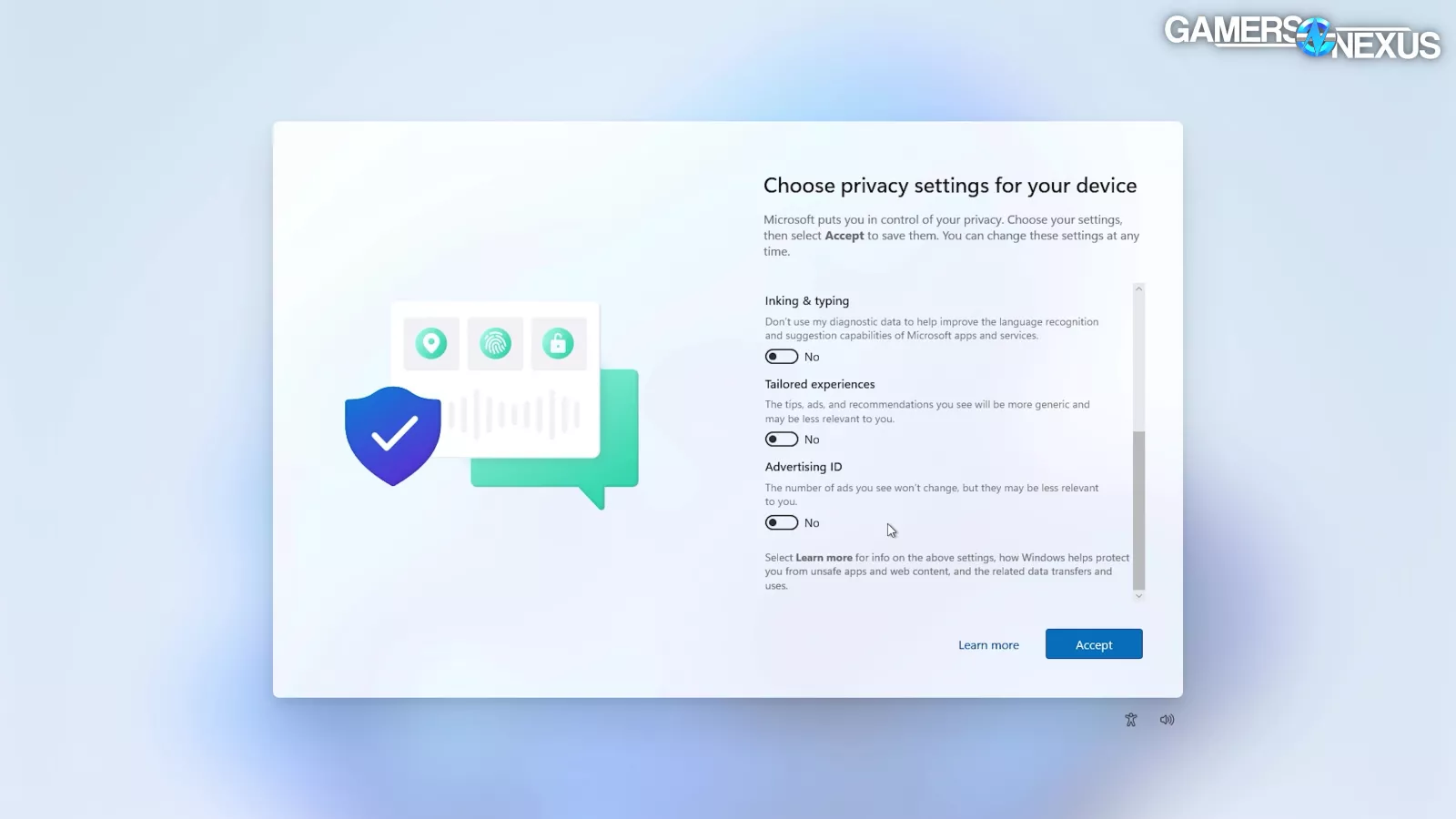

OS Setup

On to the software.

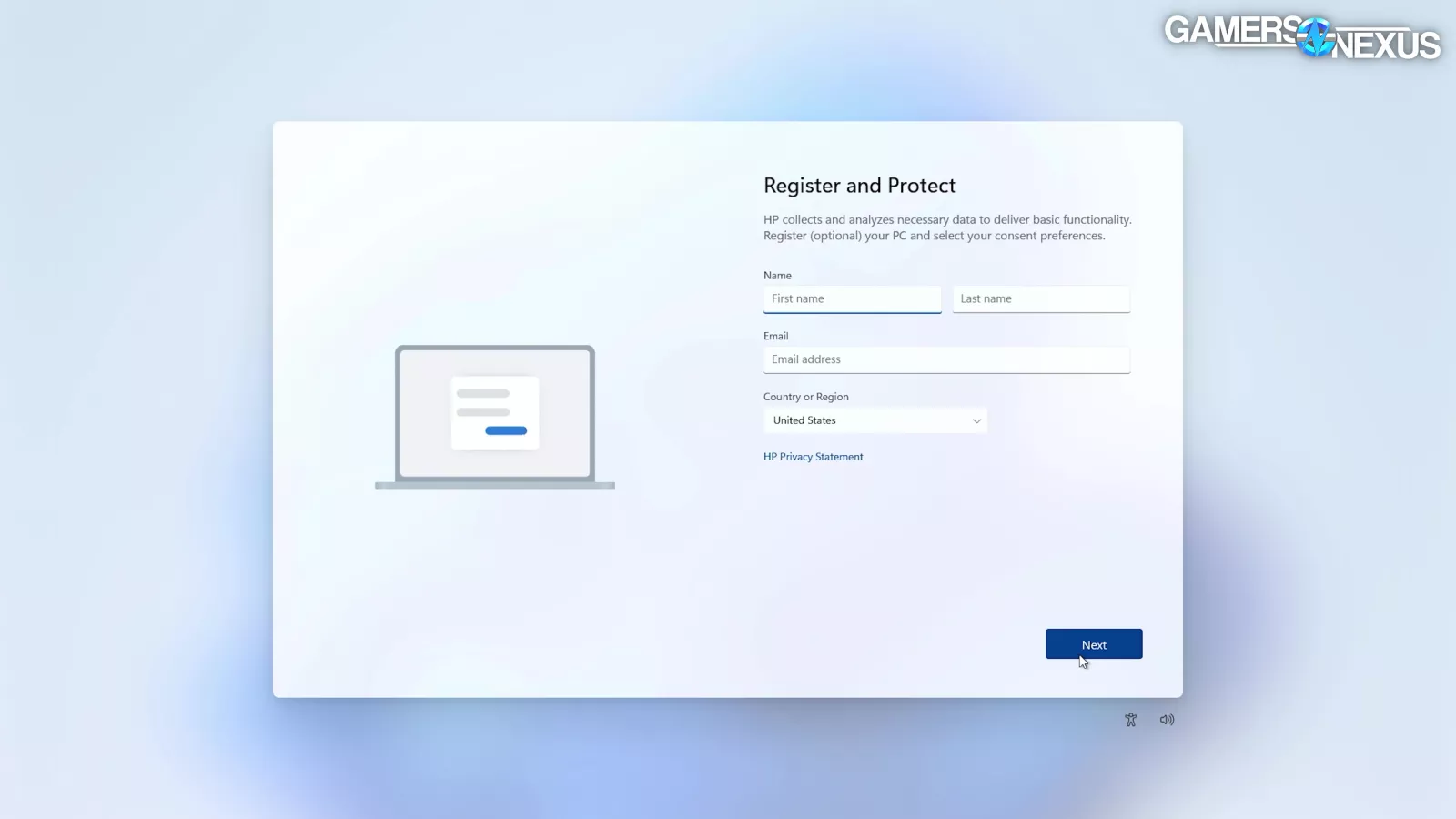

Windows 11 setup was the usual, with the added twist of trying to get us to register and give our data away to HP. Again. It’s possible to just click through these without entering anything, but the UI doesn’t make that plain – it’s a dirty trick that we’re sure works on tons of people.

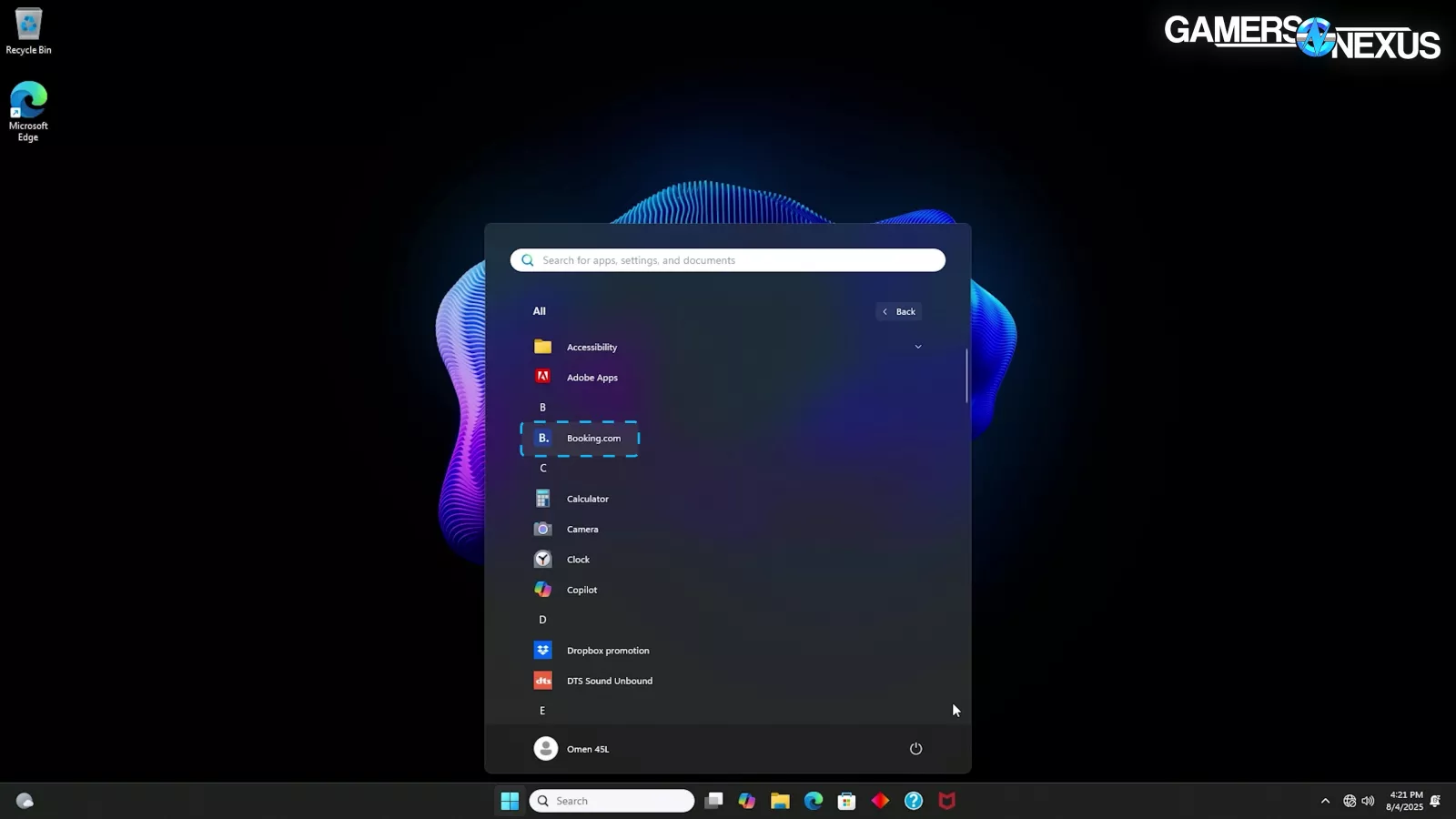

Hitting the desktop brings more disappointment. Behold the bloat: myHP, “Dropbox promotion”, Adobe Apps, and whatever Otter.ai is are pinned to the start menu. The entire apps list also includes Booking.com, which isn’t even remotely related to anything, DTS Sound Unbound, 8 different HP utilities, McAfee, and OMEN Gaming Hub. There are 16 total apps beyond what normally comes with Windows. The OMEN app and a couple of the HP ones are probably useful, but the rest are just trash that HP likely gets money or benefits for including.

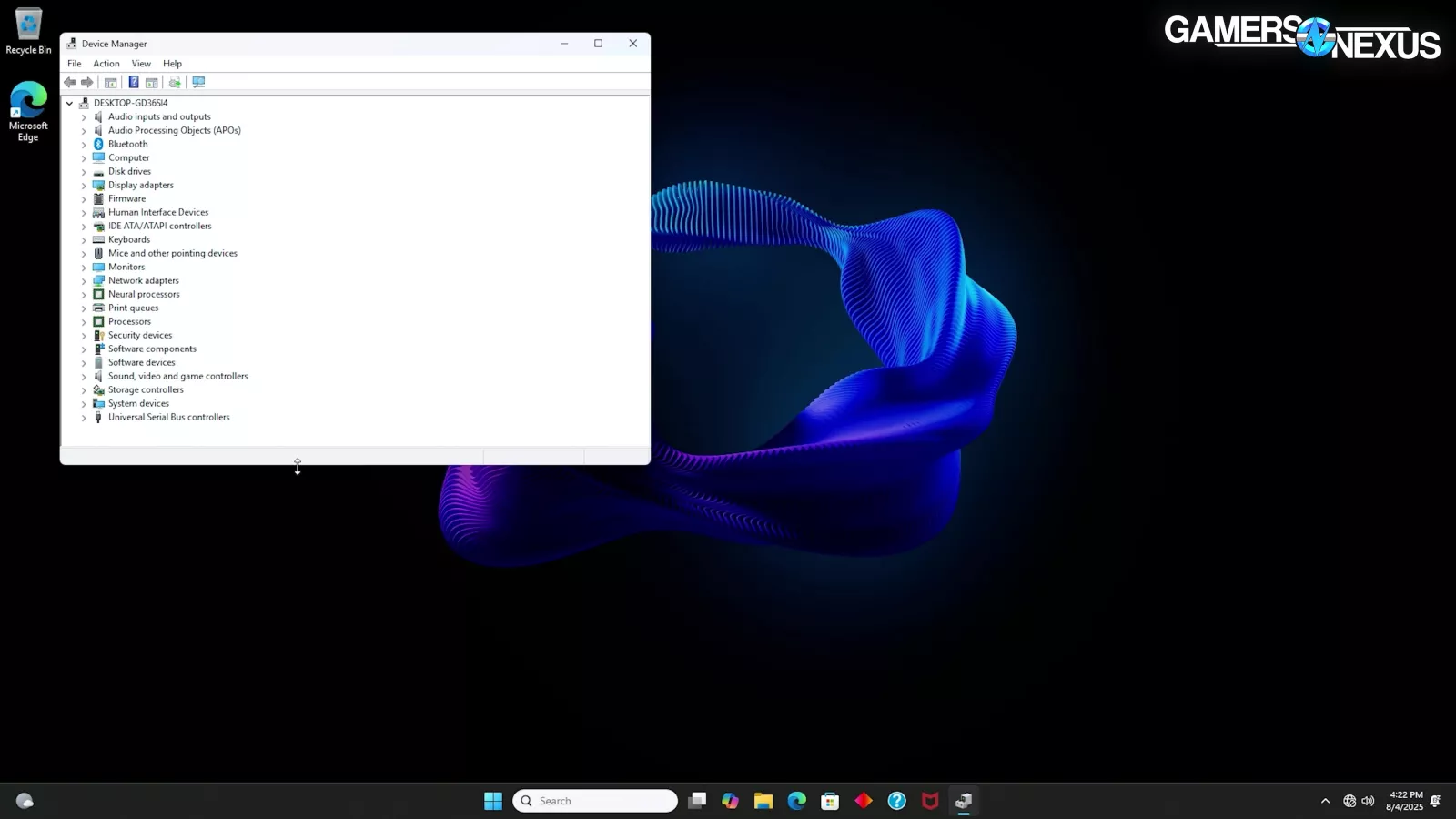

Device Manager showed no missing drivers, so that’s finally something good. If HP’s going to shovel bloat on us, this is the least it can do. The NVIDIA graphics driver is version 572.16 from the 50 Series launch at the end of January. Our system shipped at the beginning of April, so it’s missing two months worth of updates. Right back to the disappointment.

Maybe we need to start using “better than HP OMEN” when back-handing out praise.

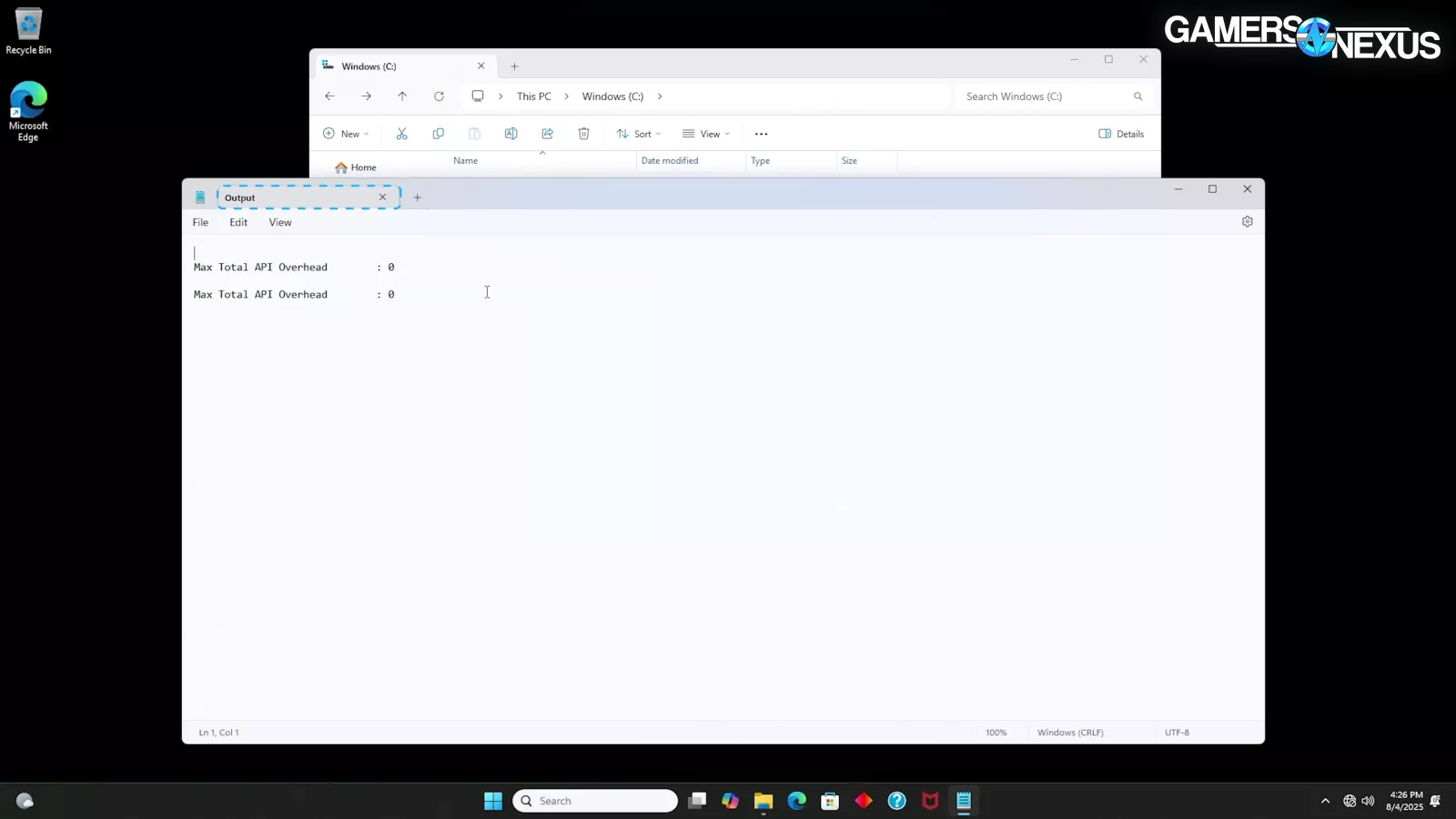

The only other noteworthy find was a file named “Output” in the C:\ drive that had “Max Total API Overhead : 0” written twice. This kind of file would normally have some kind of test results, but this seems incomplete.

HP fails at providing a clean and up-to-date Windows installation.

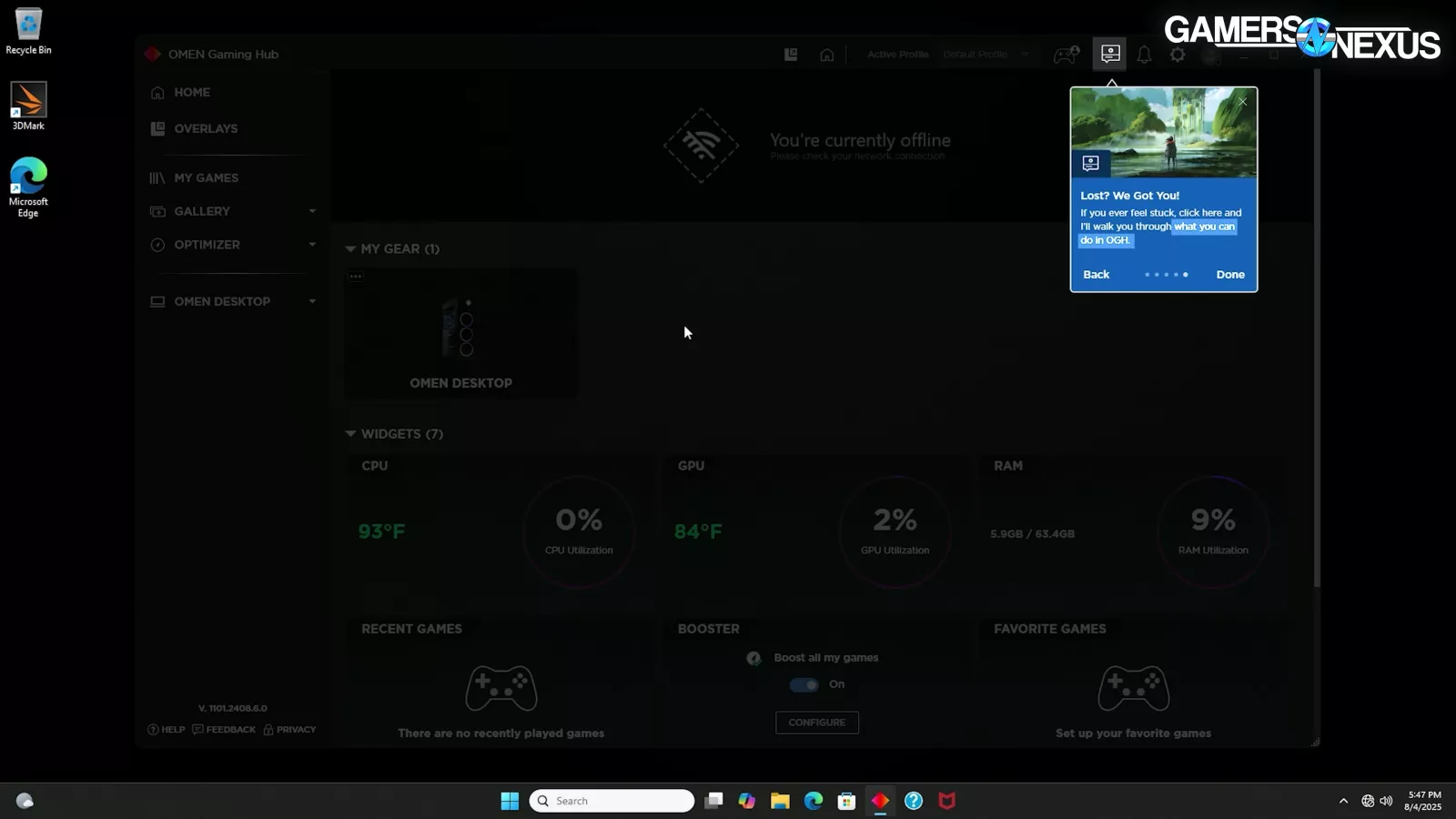

OMEN Gaming Hub

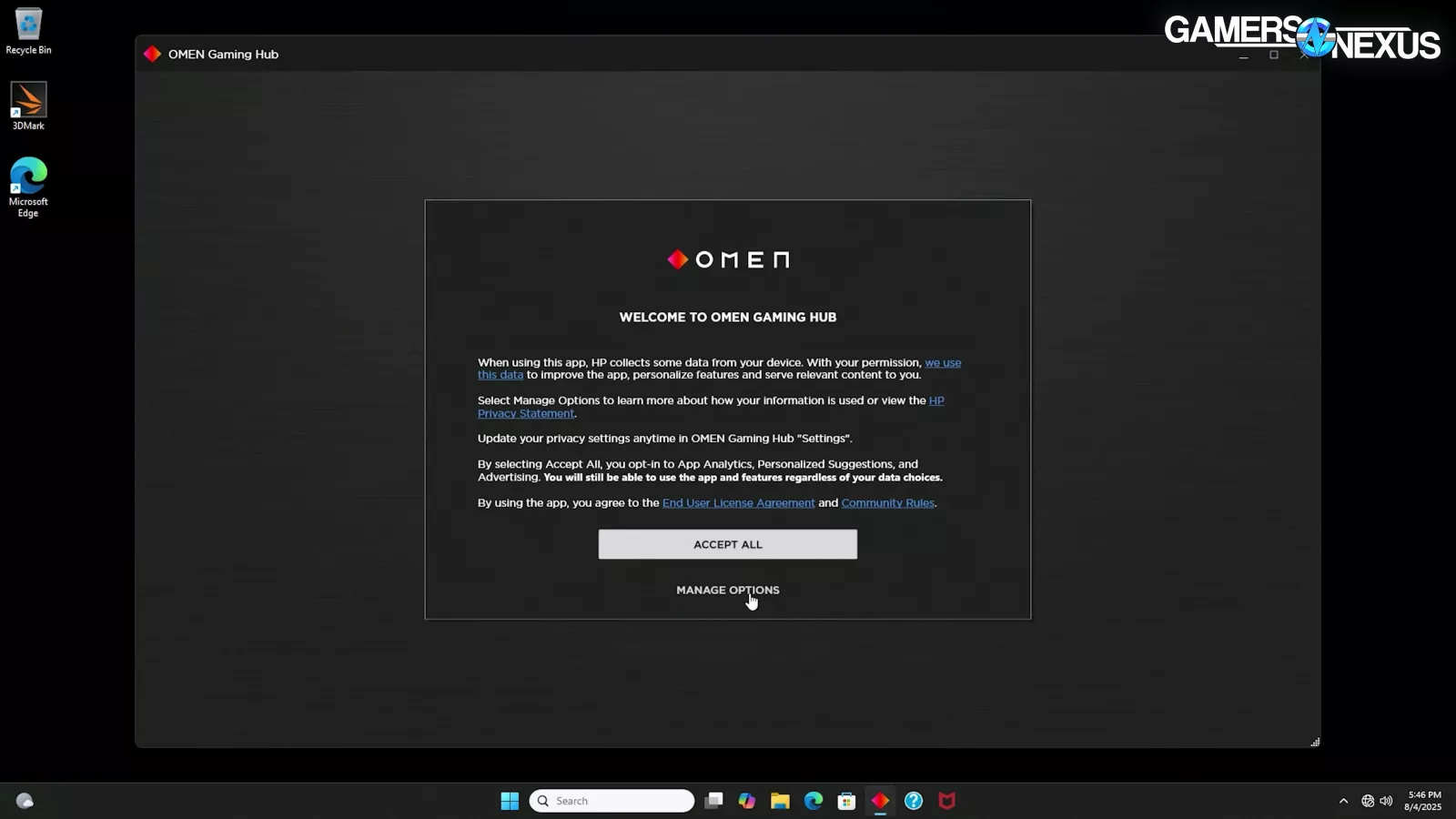

The OMEN Gaming Hub software was, uh, “interesting.” The intro dialog box had some cringey text, like “How about we elevate your gaming experience with badass capabilities?” and closing with “Go ahead and explore - we won’t bite.”

The next dialog box had even more attempts to harvest data. Opting out required clicking “manage options,” then individually toggling off App Analytics, Personalized Suggestions, and Advertising. That’s on a computer that’s about $5,000, by the way.

Then we got hit with a short guided tour of in-app popups showing us what we “can do in OGH.” Coincidentally, “OGH” is also an accurate onomatopoeia for the sound we made several times while writing this review.

After finally getting the app open, we immediately realized that it’s trying to do too much. “Game Booster,” game launcher, hardware monitoring, overclocking, keybinds, “network booster,” lighting, fan control, and yet another overlay that we don’t want are all packed into this software that we imagine is maintained by a revolving door of contract devs.

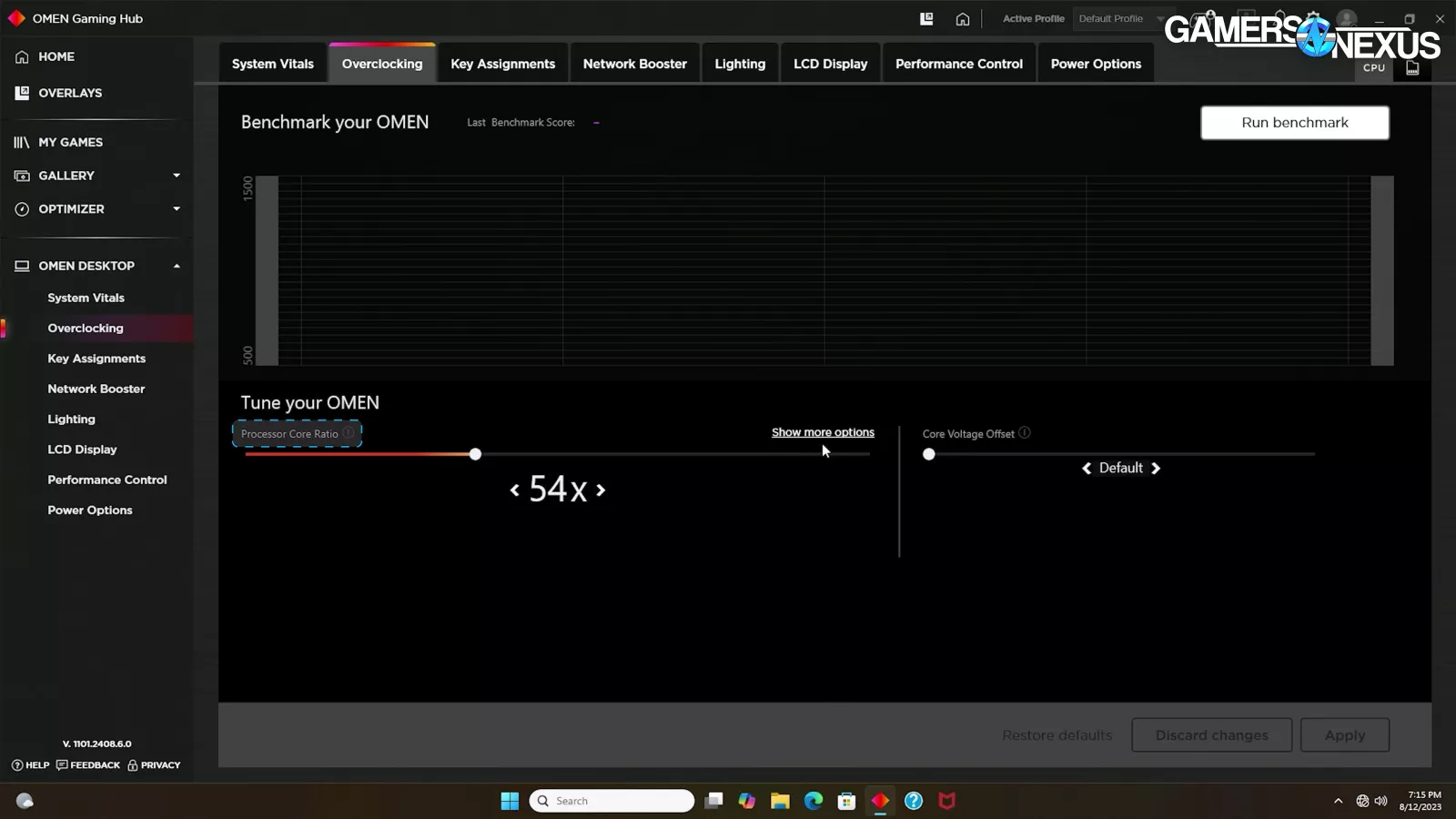

Digging into the overclocking tab is disappointing – all you get are sliders for core frequency multiplier and a core voltage offset, even after clicking “show more options.”

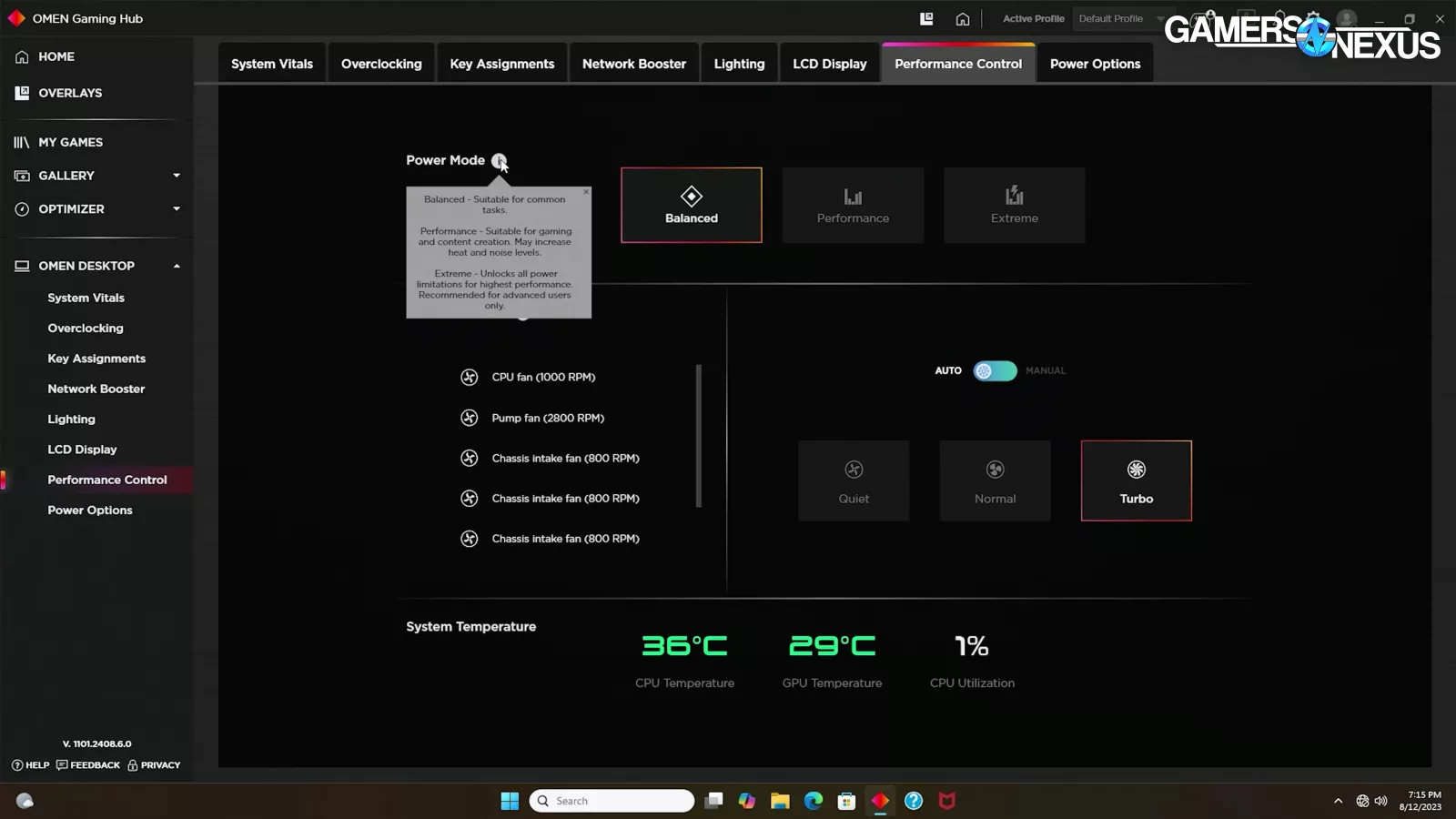

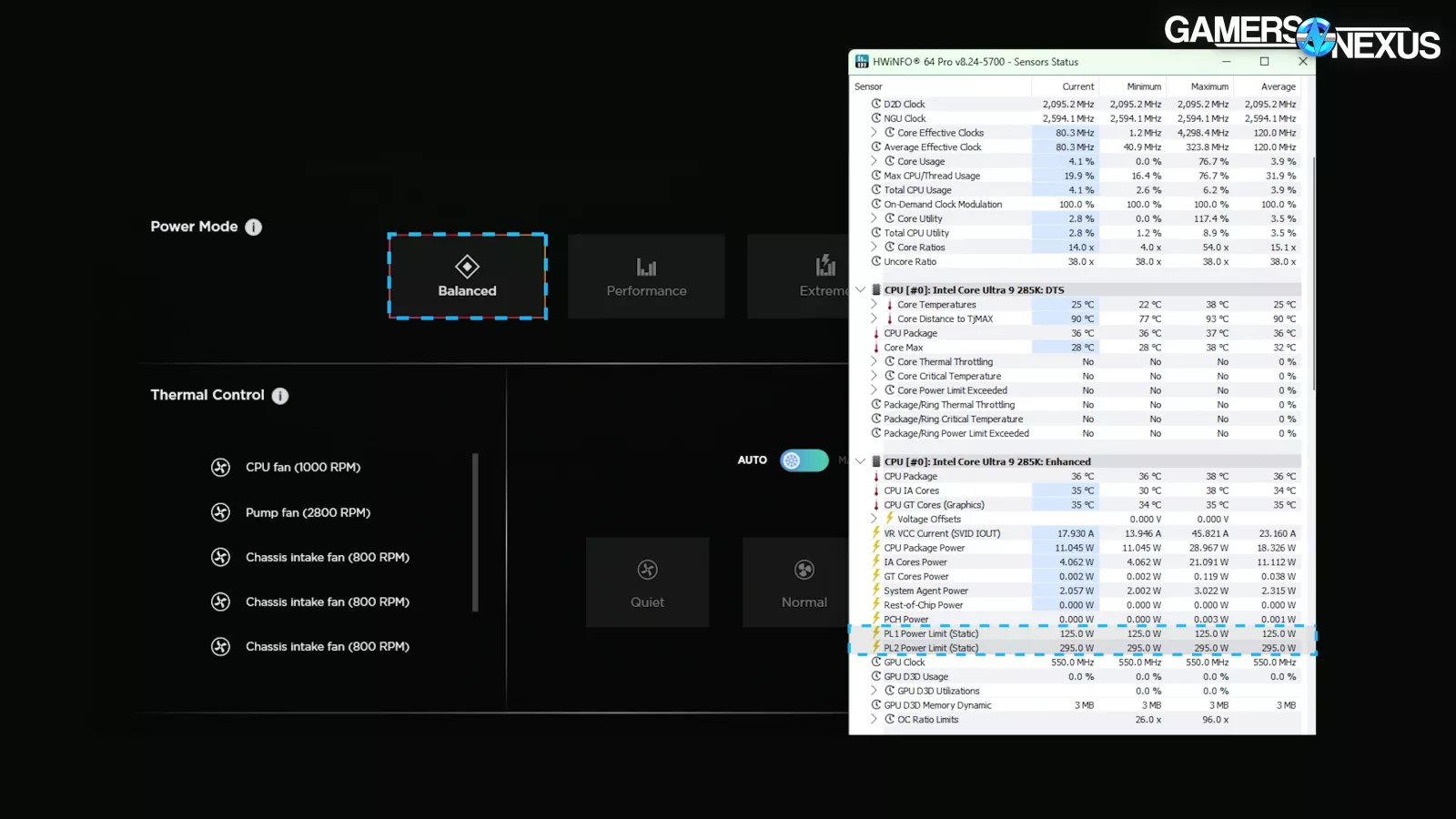

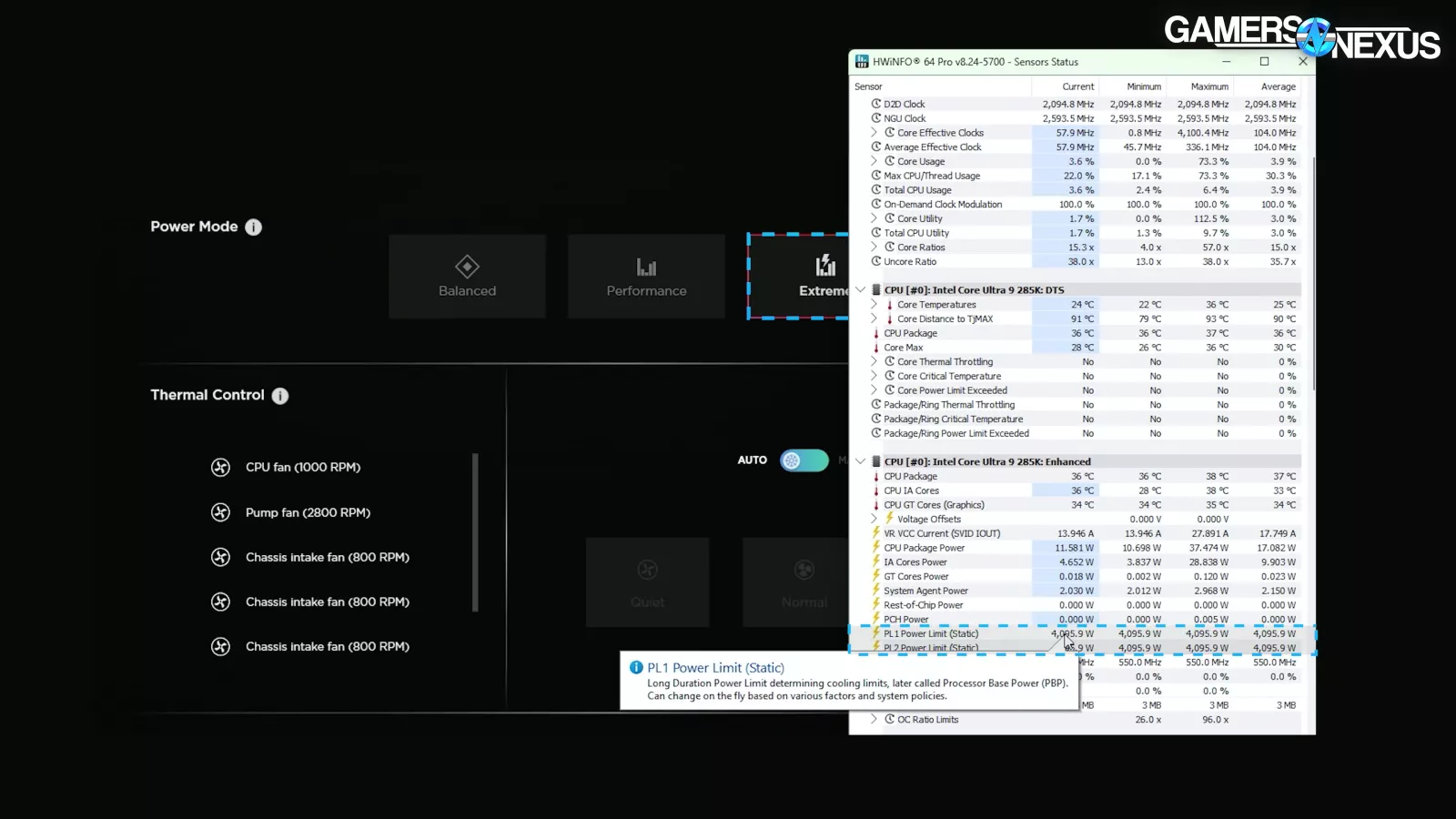

The Performance Control tab is where HP hid the CPU power limit controls, but only by way of 3 preset modes. “Balanced” is the default, setting PL1 to 125W and PL2 to 295W. “Performance” sets PL1 to 190W, and PL2 still at 295W.

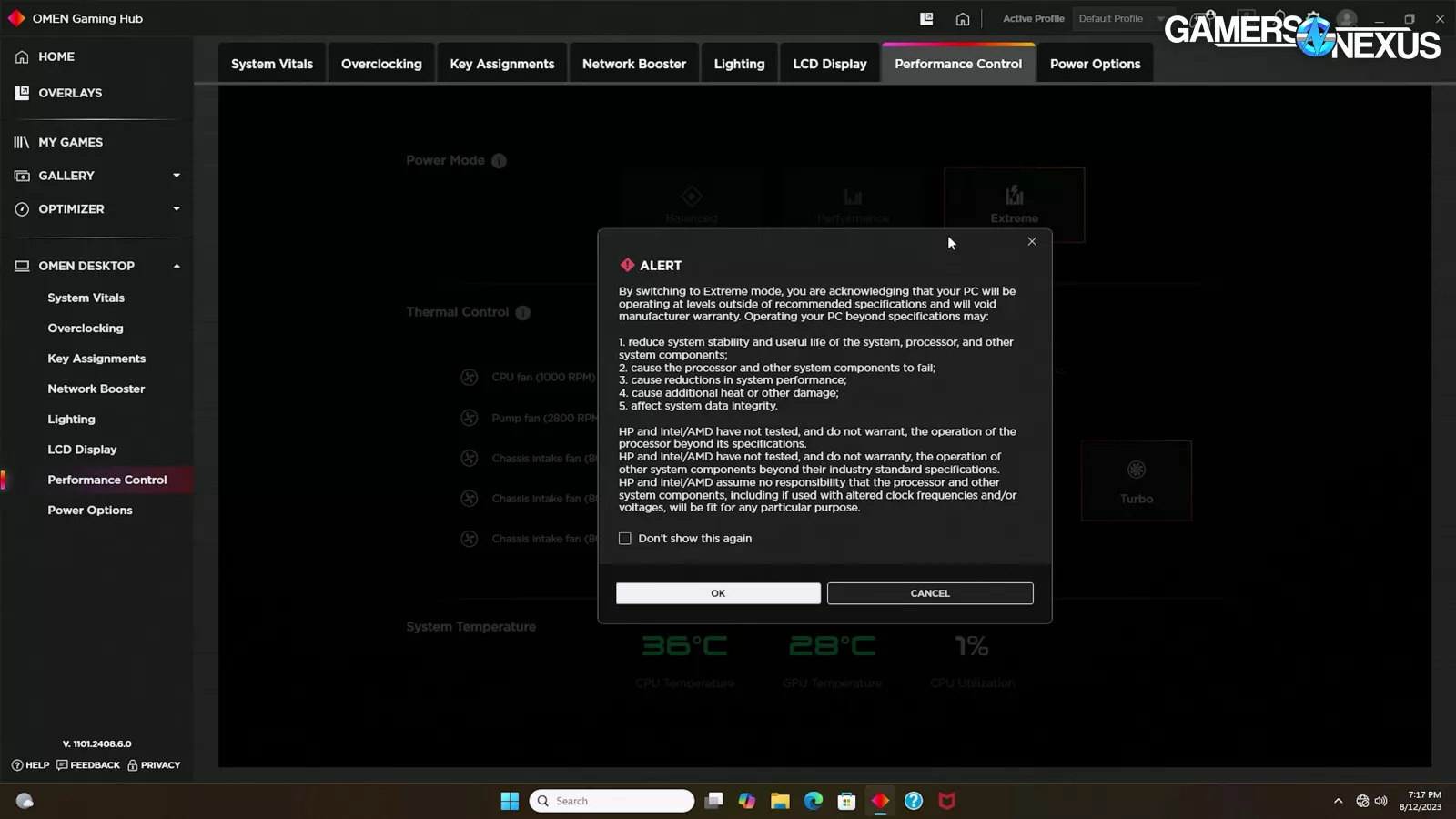

“Extreme” has to be enabled in the BIOS and gives you a warning that you will void your warranty if you use it to run the CPU at its spec. Pressing “OK” and throwing caution to the wind sets both power limits to maximum. Voiding a warranty for running the CPU how it was marketed and reviewed is certainly a choice.

The end result is that stock/balanced avoids bloatware but cuts CPU power budget in half, “Performance” uses bloatware, enables spying by HP, and still limits performance, and “Extreme” enables bloatware, spying by HP, and voids your warranty. Great.

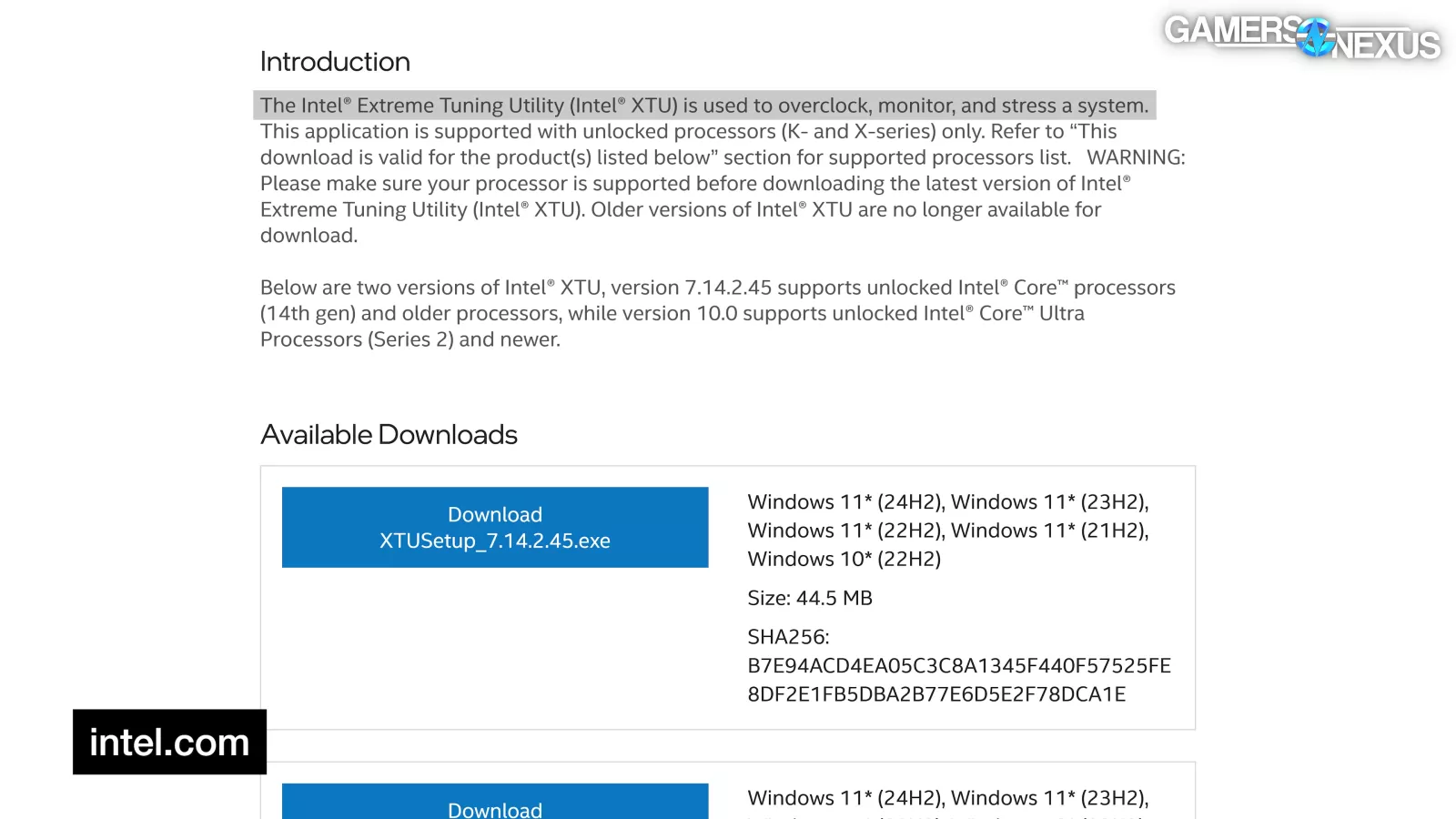

The secret 4th option is to use Intel XTU to set whatever power limits you want.

Packaging and Accessories

HP’s packaging for the OMEN 45L was good, and one of the only clear positives.

The outer box had plastic locking plugs at the bottom. There was plenty of foam and air space between the outer and inner box, which sat in a cardboard base.

The plastic plug lock company must be doing great, because the inner box also had them. Inside was even more foam.

This might seem like overkill to some people, but we actually have an older model HP Omen system that came with the glass front panel smashed. So maybe the extent of HP’s packing is a reaction to reports of shipping damage.

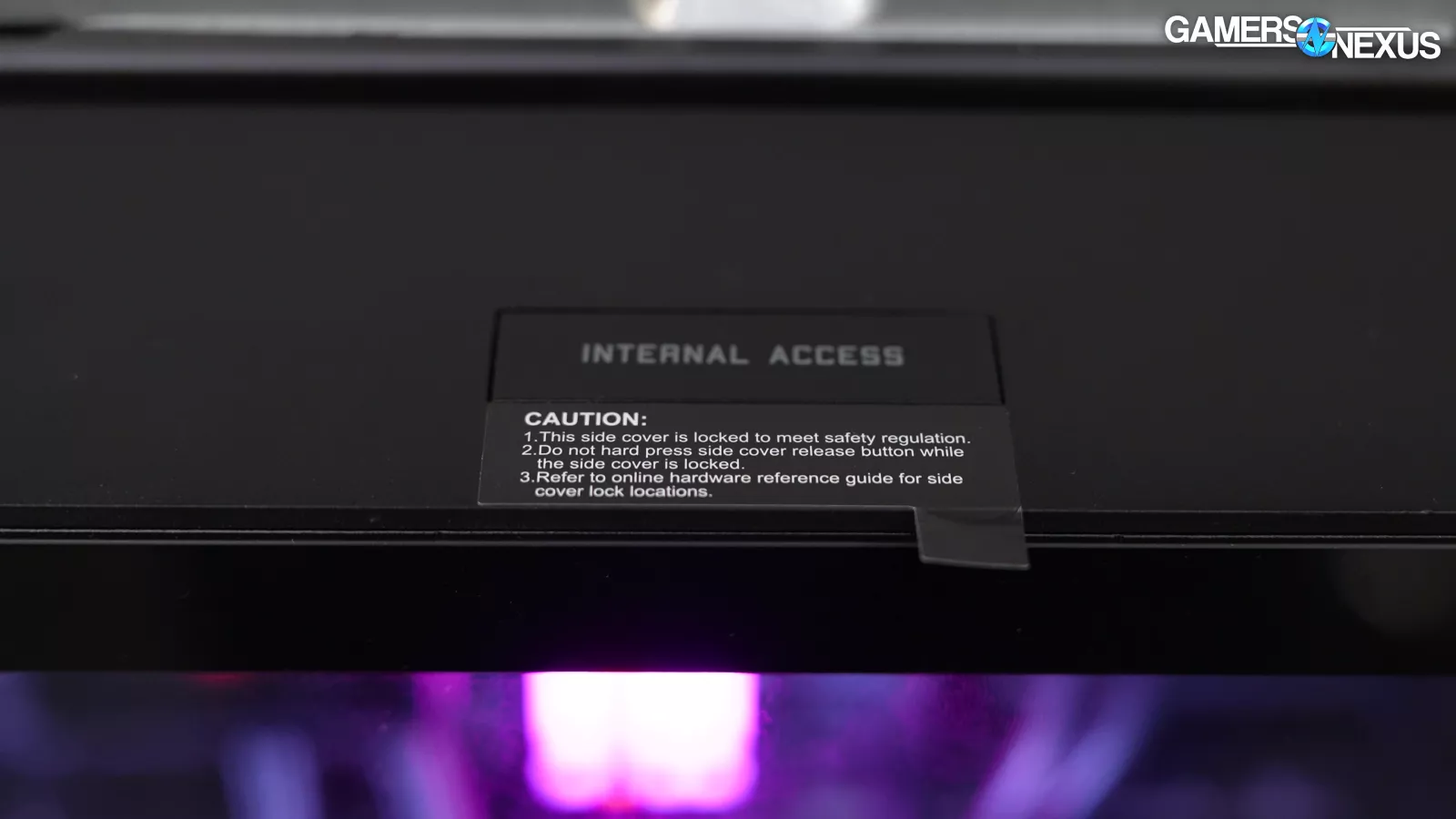

The system included an AC power cable, small quick start guide, customer support slip, and a sticker above the glass panel explaining that it’s locked for shipping. It’s pretty basic, but the basics are there.

Diagnosing the Omen

We next tried to diagnose the problems.

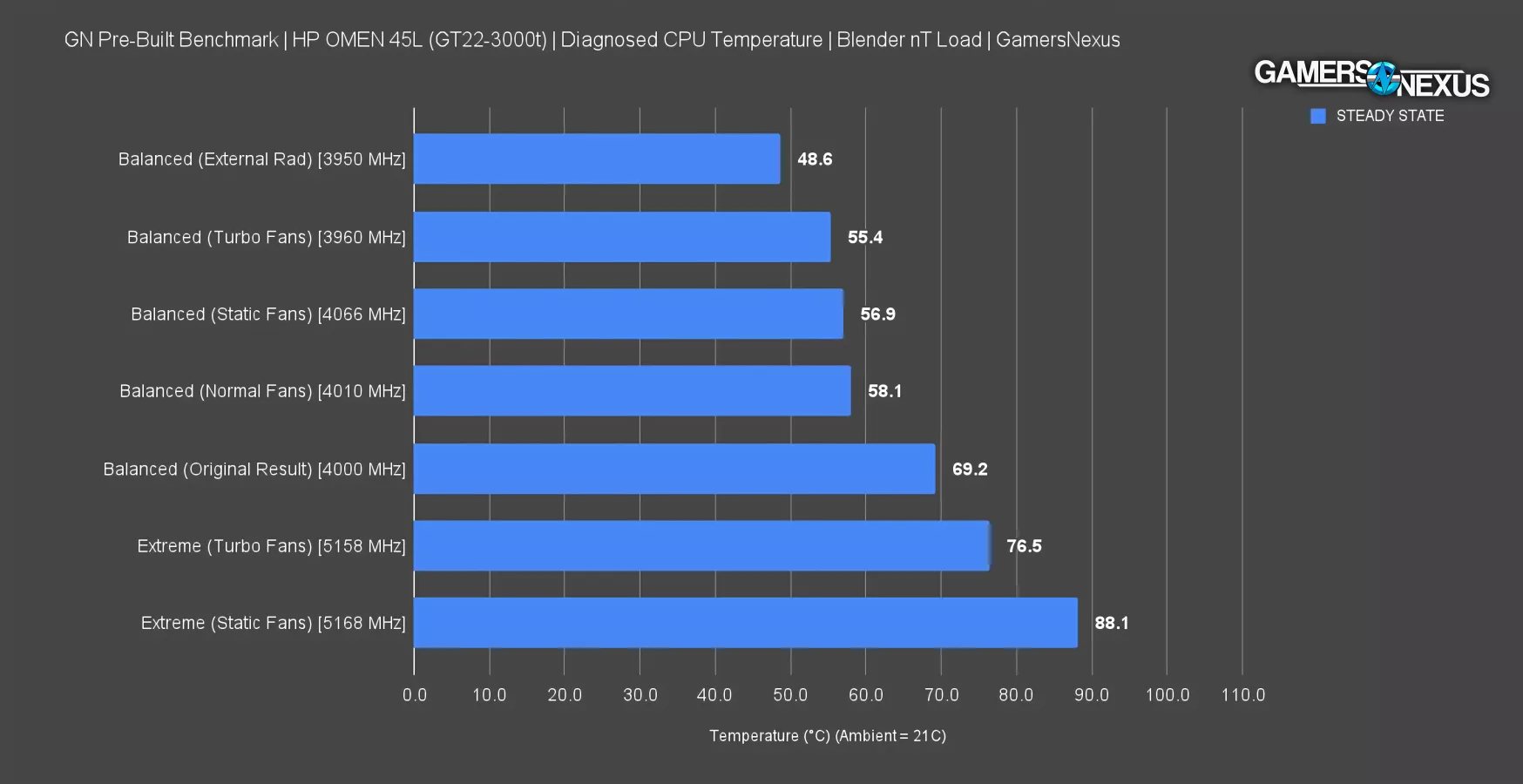

This chart shows new testing after a repaste and remount. This is at steady state, not at peak, so that means that the non-Extreme results were running at their reduced PL1 during this steady state log.

All data is comparable except the original result, which had HP’s installation. The chart also shows configuration changes for the system. The only proper result on this chart worth considering is the Extreme configuration. It’s still not at the right frequency, but it’s a lot closer; anything else is totally unacceptable for frequency. That Extreme result actually held a 77-degree average steady state CPU temperature and not shown here, but its peak temperature was lower than the peak temperature of the other tests. And that is because its pump speed is higher by default. So they are destroying the performance of the other. 77 is actually completely reasonable if only it didn’t require voiding the warranty and manually modifying the default behavior. It’s still a little slow, and it still fails the test, but it’s not nearly as ruinous. The point is that HP’s system is capable of handling the higher power load and can even cool it, they’re just choosing not to for some reason.

They might choose not to for noise reasons -- but if that’s the case, they either need to make it a lower spec CPU and cheaper price or improve the thermal performance.

Their so-called “cryo chamber” is seriously hurting performance, anyway: By removing the radiator from its mummifying wrap and enclosed tomb of impedance, we reduced the temperature like-for-like by about 10 degrees Celsius. That is a huge improvement for something that’s supposed to be “Cryo.” If HP had mounted the radiator to the front of the case and put it behind a mesh panel, it’d probably split the difference here; instead, its patented gimmick is running the system hotter, which is contributing to their likely concern of noise levels if they were to run it properly. A better radiator location and chamber would reduce temperature, which would allow them to achieve the same thermals for similar noise, which would allow them to boost the CPU frequency.

The reason the PC’s chamber sucks is because of the huge amount of impeding metal surrounding the radiator. The limited area for flow immediately between the radiator and the rest of the case and potentially some problems with air struggling to get out, plus the fact that the radiator tanks themselves are wrapped in this shroud.

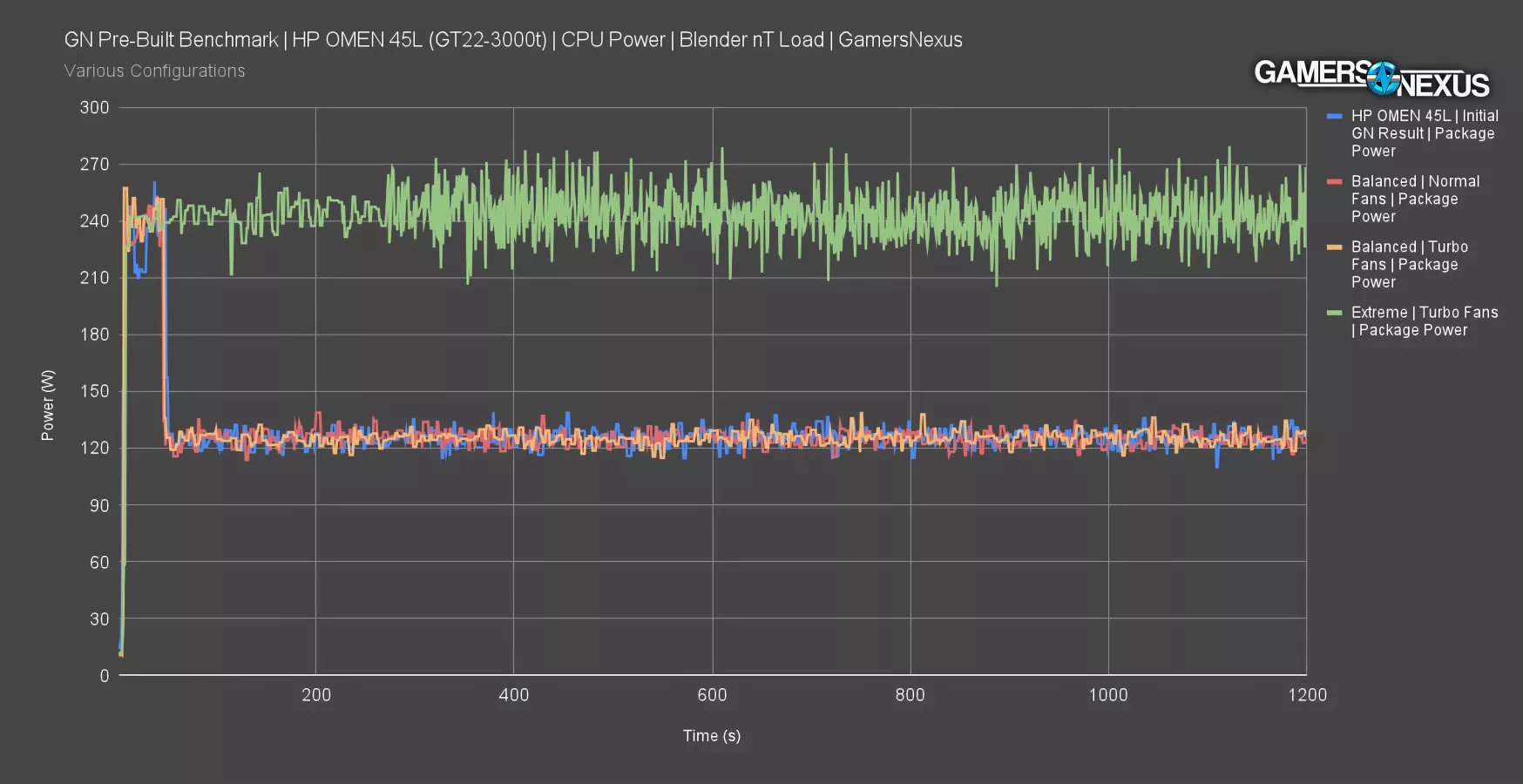

Profile vs. CPU Power

This chart shows the power consumption of the various profiles during the Blender workload. Here, the Extreme profile is maintaining its power budget for the duration of the test (rather than dropping precipitously after 50 seconds). This is the only one that should be considered for diagnosis, since anything else will be running so far below spec as a result of the power budget constraints that they’re meaningless for comparison.

Frequency Diagnosis

Using HP’s various preset profiles and some of our own custom tests, we found that the CPU frequency gets closer to stock DIY expectations -- but still not quite there -- by enabling “Extreme” mode for the power budget and “Turbo” fans. That sets the higher power limit and we’ve now admitted to voiding our warranty, apparently, but that got us to 5158MHz up from the 4000MHz range. The various other tests included a 4010 MHz entry with Balanced and normal fans and a similarly poor result with Turbo fans and balanced. The result isn’t that different with the constrained power limit.

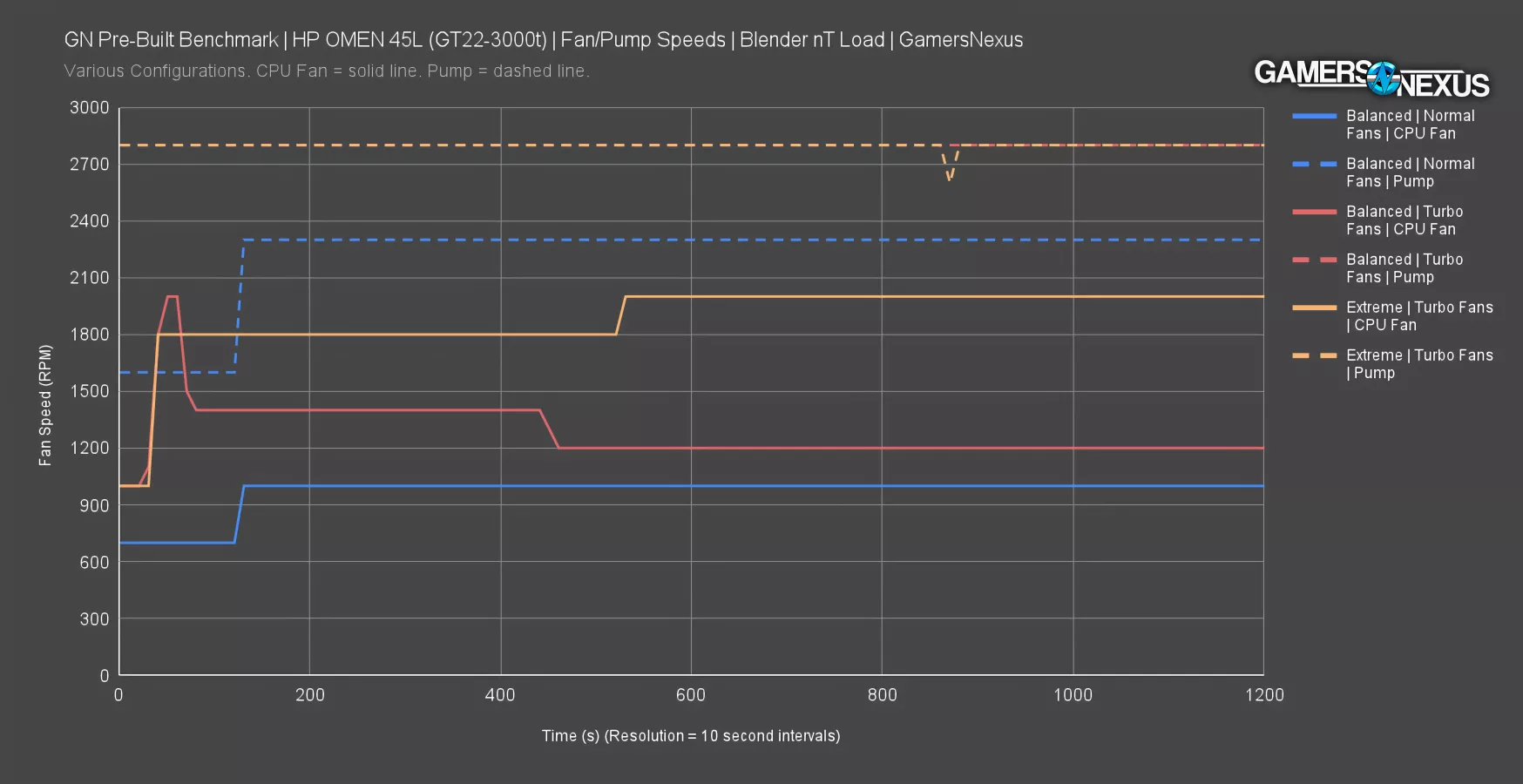

Fan/Pump Speeds

This simple fan/pump speed chart shows the speed of the pump, shown with the hyphenated line, juxtaposed with fan speed. The line colors match for the profile. The Extreme profile maintains the 2800 RPM reported pump speed for the duration of the test, which helps maintain the thermal results we just saw and the clocks closer to expectation. It still failed, but the clocks are closer.

Conclusion

We have to thank HP here because we haven't had the best products to cover over the last couple of months. And this one is also very bad, but it's so bad that it's funny and it has made our job really fun. Again, the PC is incomprehensibly bad. If you're paying $530 for a 285K and you're getting the performance of a $260 CPU, that's insane. It's also insane if you have to void your warranty to make the CPU, that is included with it, perform as it should.

The PC also has a bunch of bloatware. We didn't bother testing the bloatware impact on performance because the CPU is so underperforming that it's not going to show up. We'd have to fix the CPU first to then test the bloatware impact.

And all that is without mentioning that the plastic pump cap for the cooler was crooked. The cooler itself was not. So that wasn't part of the problem here, but the cap was. And that just looks bad for a $5,000 computer. Functionally though, there's no change.

This is the most idiotically configured pre-built PC we have tested. But we’ve reviewed it and because of that, we’re going to be changing our “It’s-better-than-Dell” award to “It’s-better-than-HP.”